This is the third of four essays in a series. A summary of the previous two is in the text below, but I recommend you read them in full here:

- Boundaries Are in the Eye of the Beholder

- Recursion, Tidy Stars, and Water Lilies

- This essay

- Carving Nature at Your Joints

Getting to the Bottom of Things

It is the urgent and greedy desire of all wastes to expand and eat up more-fertile lands: this extension of their agonised peripheries lends them a semblance of the movement and life they once possessed.

— The Pastel City, John M. Harrison

The purpose of this last essay is to make sense of purpose.

This is one of the most important things to understand about how people work: purposes drive our actions, allow us to achieve things big and small, and mystify us without end. It is the life force of our unstoppable passion for telling stories. It keeps us alive and sometimes makes us accept or even seek death. So what in the world is it?

The first impulse is to reach out for the dictionary. Head over to Merriam-Webster’s American English dictionary and look the word up, focusing only on its most relevant acceptation.

purpose (noun)

1a: something set up as an object or end to be attained : intention

Alright, but what is an “end”, then? The dictionary has an answer ready.

end (noun)

4a: an outcome worked toward : purpose

This feels a little circular, but putting the two definitions together carefully we get: “a purpose is something set up as an object or outcome to be attained.” This makes sense and matches our intuition, but it doesn’t say much at all. We would like to know where those objects and outcomes come from, what it means to “set them up” and “attain” them. The definition doesn’t give us any of that.

The Cambridge Dictionary to the rescue:

purpose (noun)

why you do something or why something exists

Yes, Cambridge. That is the question.

📬 Subscribe to the Plankton Valhalla newsletter

Having one or more purposes—chasing goals near and far—is an integral part of our lives. There is hardly a waking moment when you and I are not thinking about something to be achieved, or about the ways to achieve various things. I will go as far as saying that purposefulness is one of the most fundamental properties of human beings, and of many non-human beings too. Yet this same topic is the source of endless confusion, conflict—sometimes even angst. How does purpose work? Understanding that sounds like a good way to solve some of our thorniest problems.

The previous essay in this series prepared us to answer this question. In fact, we already began answering it a little. But let’s go in order.

In the first installment, Boundaries Are in the Eye of the Beholder, we saw how the way we think about the world—made of separate, clearly labeled “things” that you can depend on to “be themselves”—is an illusion. The universe is governed by physical laws that are all about movement, forces, warping, and never about peacefully existing in a room in the shape of a sofa (as sofas do), or revolving around the sun in highly predictable ellipses (as you and I do). We see recurrent patterns all around us, patterns we label with names like “dog”, “Africa”, and “inflation”, but they are not at all the obvious result of applying those physical laws. If you look at the physicist’s equations, you’d expect the universe to be a big, homogeneous mess of random, indistinguishable fluctuations. Why all these seemingly predictable “things”, then, and why such neat distinctions between them?

The second essay, Recursion, Tidy Stars, and Water Lilies, was all about answering that question. The answer was perhaps a bit surprising: at the most general level, what enables the formation of non-random patterns is recursion, i.e. when some phenomenon and interaction—including random ones—happens to affect its own future reoccurrence in any way.

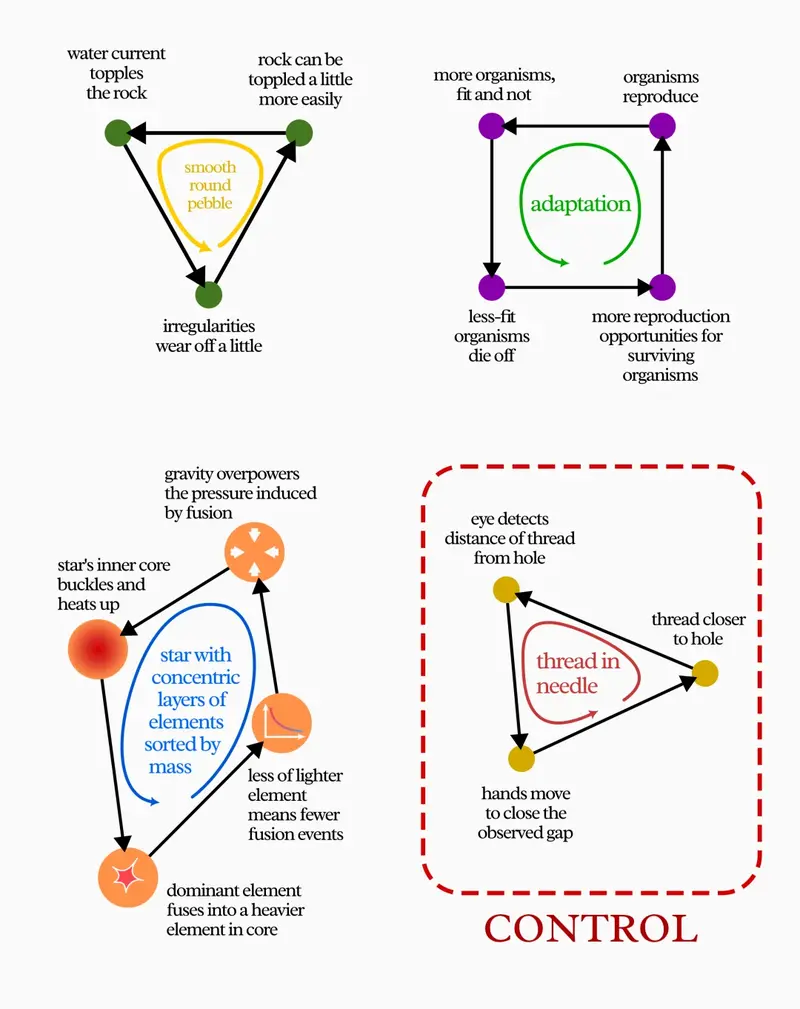

I dedicated a good part of that essay to showing that recursion is responsible for almost everything we know and understand: inanimate things like all solid matter, the structure of stars, and the shapes of pebbles, as well as every directed act and function of living things, humans included. In short, through the action of feedback loops, recursion makes things happen that would otherwise be very unlikely to happen by chance alone.

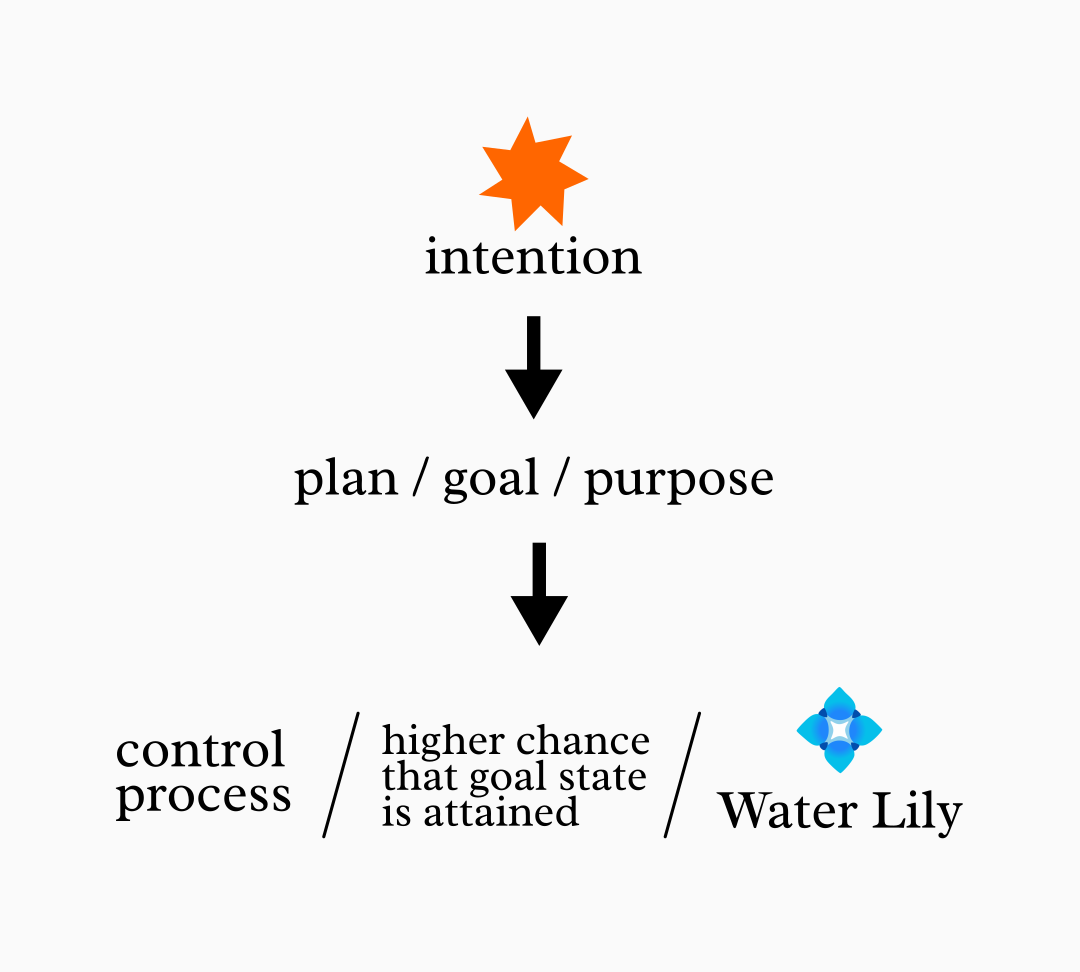

These “unlikely patterns made likely by recursion” need a name, and I’m calling them “Water Lilies”.

Aside: Why “Water Lilies”? 🪷

Previously, I wrote about a few of the countless feedback loops that allow a water lily plant to become what it is and do what it does. My conclusions were:

The plant’s DNA isn’t a script to be executed, then, but a survival kit. It sets up the feedback mechanisms, and the plant uses those to improvise.

This means that the plant is the collection of its self-reinforcing and self-regulating processes. There is no separate architect or builder, only a thing blindly constructing itself with inputs from its environment.

I chose the image of this aquatic plant to represent the much broader category of all phenomena that “blindly construct themselves” like that—not only a flower blooming but also a star stratifying, a population revolutionizing its government, and almost every other phenomenon you can think of, from the very simple to those too complex to wrap your head around. They are all Water Lilies in this sense.

I always write the name of this new concept, “Water Lily”, capitalized to distinguish it from its namesake plant, “water lily”.

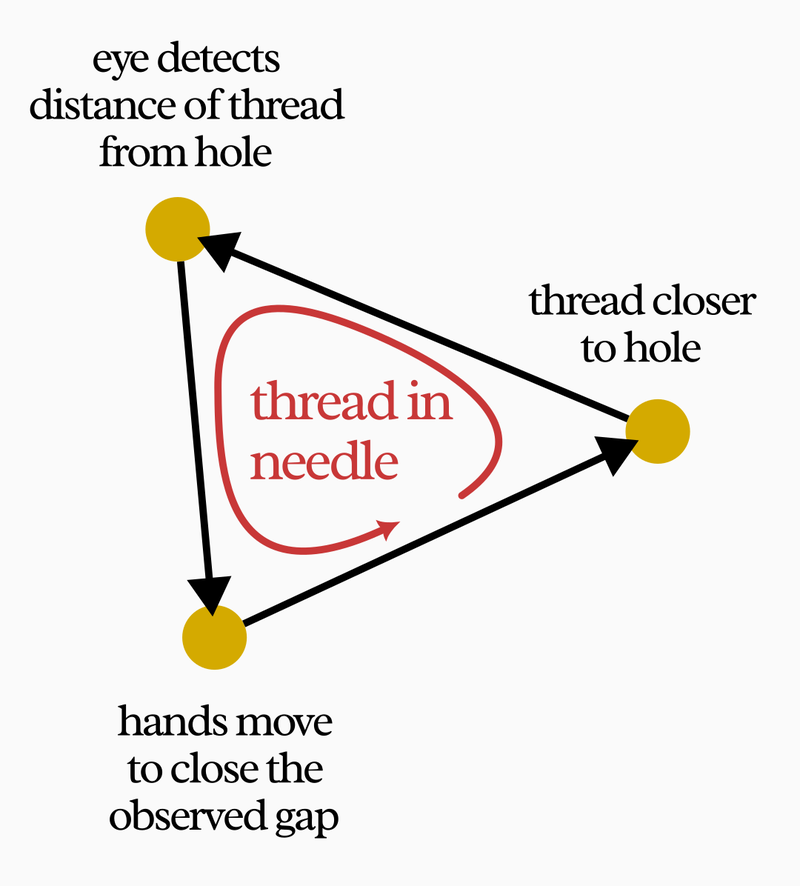

Here we are finally at the core of the matter. The feedback loops that enable recursion are exactly the same kind of process that happens in “control mechanisms”—both the engineered kind, like thermostats and cruise control, and the biological ones, like the hand-eye coordination needed to manually thread a needle. “Control & goals” are merely a special case of “feedback & Water Lilies”.

In what follows I will show you the ways in which they are special. The distinction between purposeful behavior and purposeless phenomena is not in whether recursion happens (it does in both), but in how recursion affects us. We’ll see that some objective properties of those recursive processes matter a great deal when goals are involved, and not at all when they aren’t. Even the ways we humans must engage with those purposeful loops is entirely different.

Once that is cleared up, the contours of purpose will be clearer, and the surrounding confusion much reduced. Not only that: we will get, almost for free, new clarity on other important-but-murky concepts like “meaning” and “information”.

All this will finally lead us back to our first doubts from more innocent times: where do those boundaries come from? This is the topic of the fourth essay, Carving Nature at Your Joints, published separately.

We humans live and breathe purpose, but we often interpret it very wrong. A little more lucidity can only help. But first, how do we know that we misunderstand purpose despite ourselves?

Table of Contents

- Part 1: The Ills and Woes of Seeing Purpose Where Purpose Is Not

- Part 2: Purpose from First Principles

- Part 3: Purpose Paths and Purpose Networks

- Part 4: The Proper Place of Purpose

Part 1: The Ills and Woes of Seeing Purpose Where Purpose Is Not

I’m not sure what this is all about, but apparently it’s God’s will that you leave this world.

— Mormon fundamentalist Dan Lafferty’s words to his 24-year-old sister-in-law before slitting her throat and her baby’s. (From Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith, by Jon Krakauer)

A Civilization of Purpose-Dreamers

Humans seem to really, really want to find the purpose of things. This has the nice effect of making us “storytelling animals”, because every story is the chronicle of intents fulfilled or thwarted. But the same tendency is also the cause of many of our self-inflicted torments. This has been going on for a very long time.

For the ancients, everything was imbued with intention—everything and everyone had a specific role and a reason to behave in a certain way. The Sumerians believed that people were built to support gods grown tired of working. They were a civilization of self-proclaimed slaves, and their social organization reflected that belief, with mandatory unpaid work in temples and in public projects. The Ancient Greeks, one or two millennia later, believed that earthquakes were caused by an angered Poseidon. After each disaster, they performed animal sacrifices, offerings and appeasement rituals—wasting resources precisely when they needed them the most.

Faith in deities was clearly a major factor. How many holy wars, following the presumed will of one god or another, have been waged throughout history? How many major life decisions have been taken based only on the belief that God wants it, or that God is there to make things right?

But religions shouldn’t get all the blame, because this human tendency to dream up purposes has always been a vice of scientific minds, too. When Kepler first proposed his new theory of elliptical planetary motion in 1609, he faced resistance by his peers, who preferred to believe long-dead Aristotle: celestial objects seek perfection, the Philosopher said, thus their goal must be to draw perfect circles in the sky.

Similar resistance to new discoveries continued through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and even into the twenty-first. At every step, scientific progress was hindered by this strange human desire to find and participate in plans that never existed.

Politicians and militants don’t fare much better than religions and intellectual circles when it comes to attributing purposes accurately. Social Darwinists justify their ideology with the purported moral imperative of “biological progress”, which has gifted the world with atrocious practices like eugenics, racism, and fascism.

Outside biology, this idea of “progress as a goal” has brought enormous harms on society by justifying colonialism and imperialism. The European conquerors believed they were on a benevolent civilizing mission, bringing the “advancements” of Western societies to the “stagnant” and “retrograde” cultures of their victims—whether those cultures asked for it or not.

But are we better today than our ancestors at keeping a balanced view of what does and does not constitute a real purpose? Not in the least!

I won’t even get into the big modern conspiracy theories, except to point out that they are all, by definition, variants of the idea of a “grand hidden purpose” at play at the expense of their believers. But even excluding conspiracists, modern people are prey to purpose-dreaming just as often—and as badly—as those that came before us.

Take superstition, for instance. According to a 2020 survey, approximately 25% of U.S. adults and 62% of German adults self-identify as superstitious. Although not all forms of supersition are beliefs in nonexistent goals, most of them are. For example, according to an Indian poll, 60% of patients believe that their health is at the whim of luck or supernatural forces: hidden plans and purposes. It is fair to assume that the numbers are in the same ballpark in most other countries.

Often, such beliefs directly or indirectly harm those who hold them. In some documented cases from India and Nigeria, people were observed delaying medical treatment in favor of traditional healing practices relying on the intervention of spirits and gods, increasing the mortality rate of preventable diseases. Also, Belgians and Americans who self-identified as superstitious reported feeling more helpless and fearful during the COVID pandemic. Belief in the supernatural also exposes people to exploitation by gurus, who force their followers to “donate” money and labor, and emotionally blackmail, coerce, sexually abuse, depress, and traumatize the majority of them in the name of grand divine schemes.

Although society is indeed full of purposeful behaviors, where actual people and other creatures do things with real, specific intents, that doesn’t seem to be enough for us. We thirst for more goals, higher purposes to dance to, and we seem to find them in virtually anything we see—living or not, understood or not. But hallucinating a nonexistent goal is harmful for us and others.

Why do we do it, then? Why do so many natural phenomena seem to behave as if someone had wanted and planned them? How can we keep hurting ourselves like this, after all the pain we have inflicted on ourselves?

More Questions from Science

Scientists call this tendency to see purpose everywhere “promiscuous teleology”, where “promiscuous” means indiscriminate and “teleology” is the technical word for interpreting things as if they had a purpose and are working towards specific goals.

The first strong hints of inborn promiscuous teleology come from a large number of studies on children’s thought processes. We know that children display much stronger teleological (purpose-based) thinking than adults. For kids, everything seems to have goals: mountains are there to be climbed and the night comes to let the sun sleep. Recent research suggests that the tendency might be hard-coded in our very genes.

Promiscuous teleology decreases with age, but never goes away completely. People with less schooling and scientific education tend to be more teleologically promiscuous, for instance. Even educated people, in times of mental strain, lean more into purpose-rich interpretations, and Alzheimer patients do it almost as much as children.

All of these results paint a coherent picture: seeing goals everywhere is the natural way of being human, and it takes years of practice and constant focus in order to keep this propensity temporarily at bay.

Cognitive scientists hypothesize that each of us has a “hyperactive agent-detection device” somewhere in the brain—a neural module especially evolved to recognize intentional actions around us—sometimes appropriately, sometimes a little too eagerly.

But, again, why?

Why might humans have evolved this kind of a reasoning strategy? Lombrozo has several ideas. “One possibility is that if you look at our evolutionary past or at our experiences growing up, one of the things we did most often was explaining human behavior. And human behavior is generally goal-directed — it does involve intentions and functions. We may be taking the mode of explanation that we’re best at and then applying it to other domains,” she says. “Another possibility is that it’s more effective. We’re going to learn more about the world if we go around assuming that things have functions and then sometimes discovering we were wrong, rather than the reverse.”

— Cognitive scientists Tania Lombrozo authored several of the above-mentioned studies. Interview by Hania Köver, UCBerkley News.

Finding the goals underlying various happenings is an excellent way to understand the world—when and where goals do exist.

The English word “why” (as many analogues in other languages) perfectly encapsulates this deep-rooted confusion. We use it in two very different meanings without even noticing. In some cases, asking “why?” is a question about the past causes of an event, as in how come?:

Why did the parasol fall?

Because a gust of wind dislodged it.

In other cases, “why?” is asking about goals in the future, as in what for?:

Why were you running?

Because I needed to catch a bus.

Often, you can tell which of these two meanings applies, like in the two examples above, and no harm is done. Sometimes, though, things are not so clear-cut:

Why aren’t people born with wings?

Why did those countries enter war?

Why did he hit his wife?

Do these questions warrant a how come answer, or a what for answer? There is a vast part of reality where the distinction between mindless causes and intentional action is far from obvious.

Even the scientific advances I cited above haven’t fully cleared this picture yet: what exactly does our hyperactive agent-detection device catch, when it triggers a false alarm?

To answer that, we need to understand what purpose is, and how it differs from non-purposeful Water Lilies.

Part 2: Purpose from First Principles

The previous essay ended with this curious definition:

A Water Lily is the particular state, out of many possible, that a system tends toward as the result of a feedback loop.

In a fully random world, none of the possible states is more probable than any other unless recursion happens. Recursion, here, means the property of a process to affect its own outcomes over time, implying a feedback loop. When the result of a process causes that same process to happen in a specific way the next time around, that means that cause and effect form a loop.

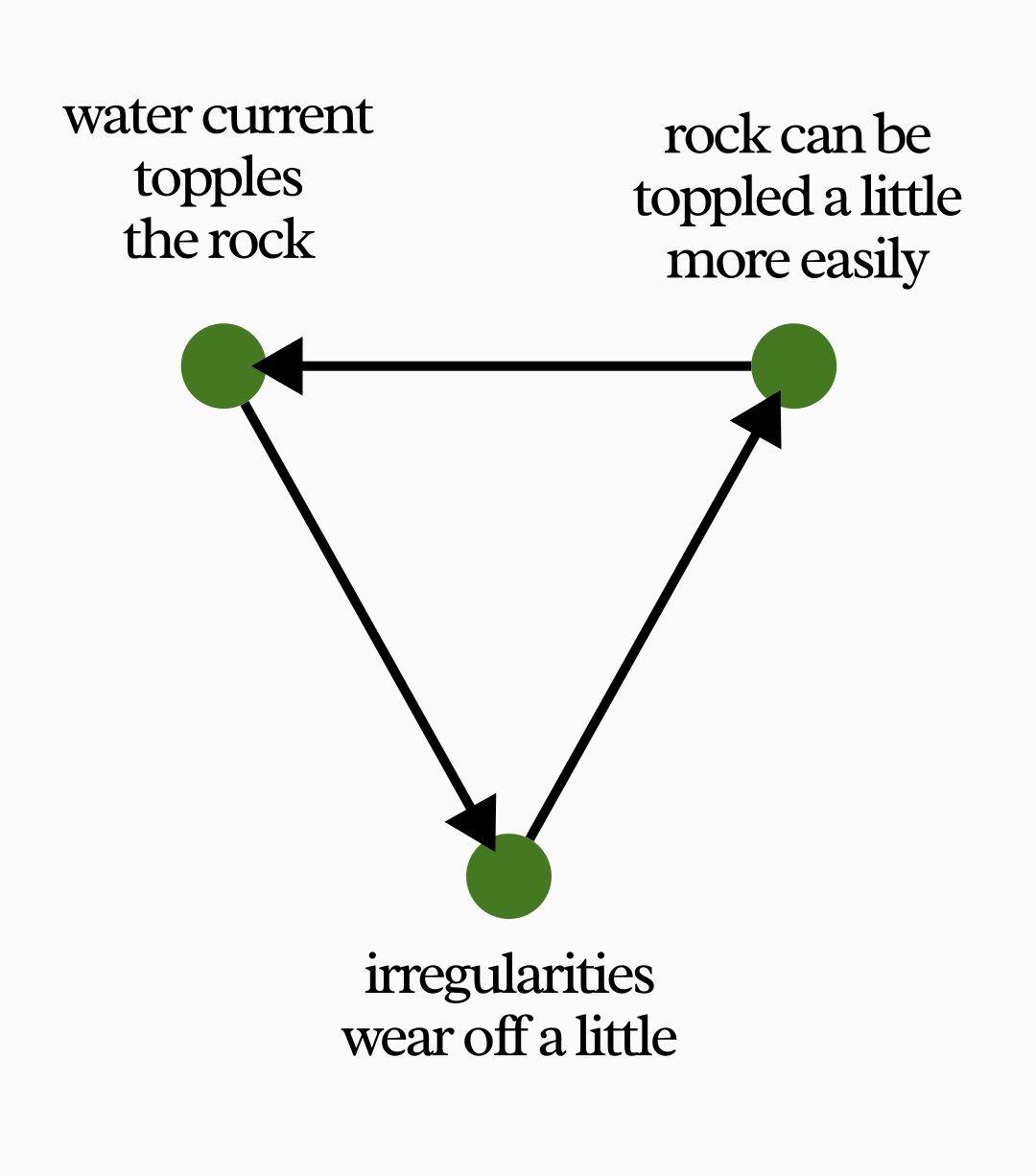

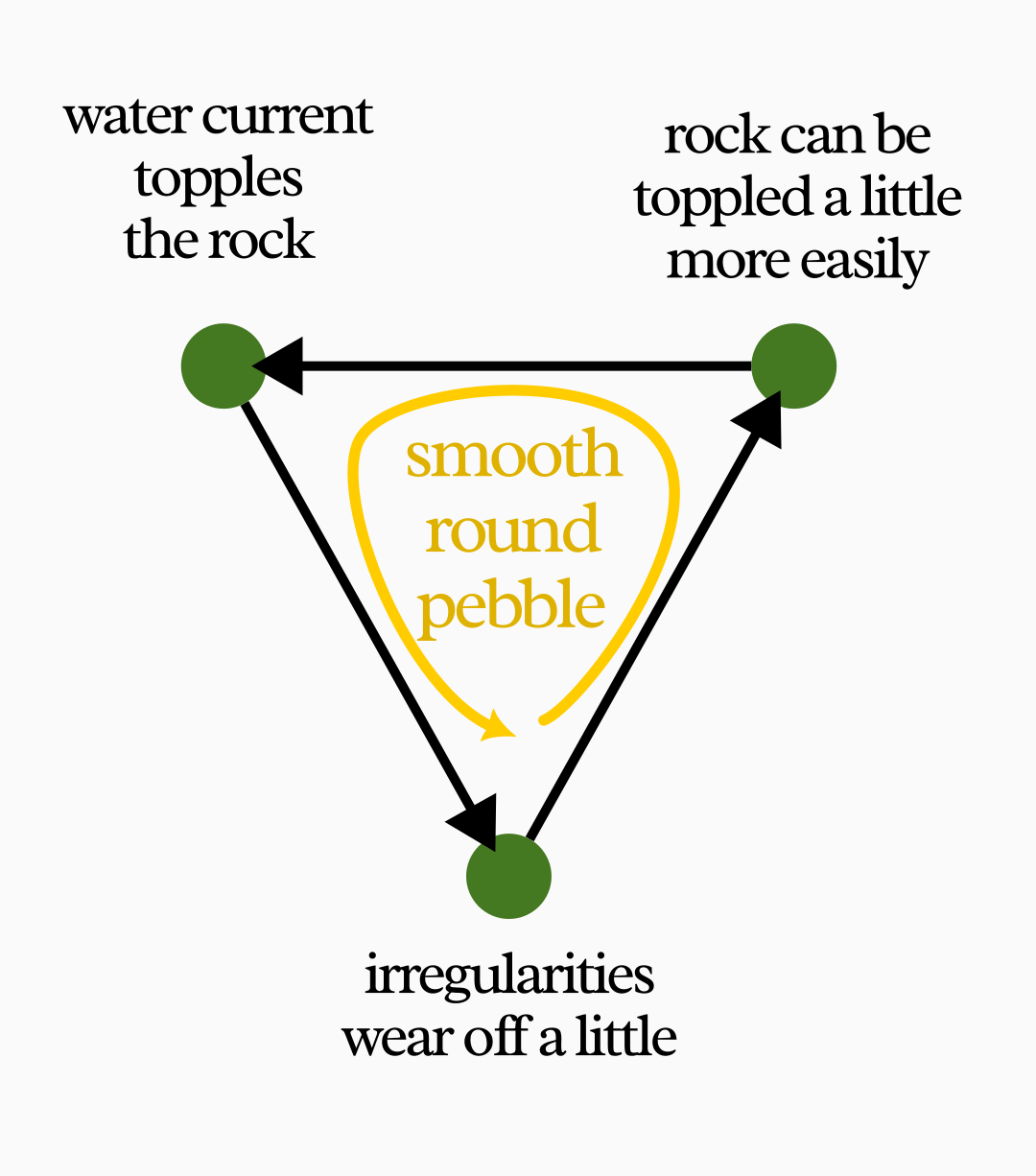

Remember the example of the rock tumbling under the waves on a beach: while tumbling, the rock’s sharp edges and protuberances rub against the surrounding rocks, wearing off a little bit at every turn; this reduction of sharp edges allows the rock to tumble more easily, wearing off its irregularities even more; and so on, until the rock is smooth and completely edge-free.

The edge-free pebble is a Water Lily, the otherwise-improbable outcome of a recursive process.

In general, then, Water Lilies are mindless results of random recursion. They literally just happen.

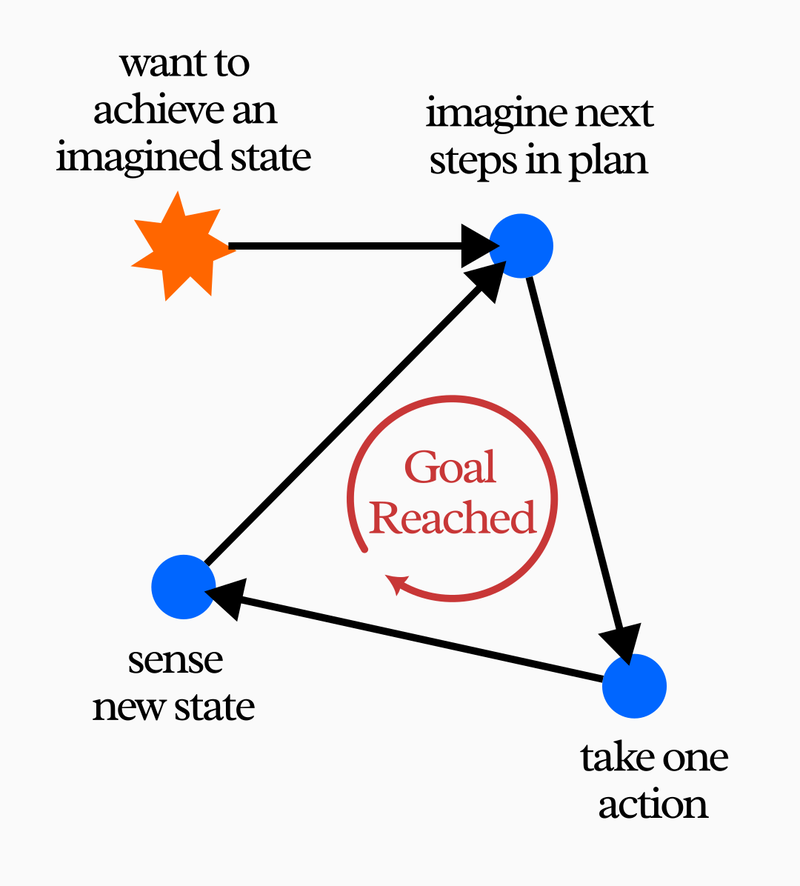

Goals, on the other hand, are special cases of Water Lilies in which human intent is involved. Here is a parallel definition:

A goal is a particular system state that a human wants to achieve by avoiding all other states

the process used to achieve a goal necessarily involves feedback, and we call it a control mechanism

The “that a human wants” part of this definition is the key difference that makes this a special case, one kind of recursion out of many.

(This might also apply to some animals, perhaps all mammals and several other intelligent species who can pull off the same kind of tricks with their minds, but we don’t know much about that yet because they can’t talk. I’ll keep things simple and only talk about humans here.)

Every intentional action you take is a control process. You can’t help it. Even seemingly instinctive acts like scratching your nose are very unlikely to happen without the enormous amount of control loops in your nervous system and muscles. Every instant, you keep adjusting the trajectory of arm and fingers based on feedback, using your body’s ability to sense its internal state, called proprioception.

Individuals with impaired proprioception, who can’t benefit from such feedback, have trouble doing elementary actions like sitting and walking straight. They bump into things often and appear clumsy with their actions. We just don’t realize how heavily we rely on recursive loops to do everything we do.

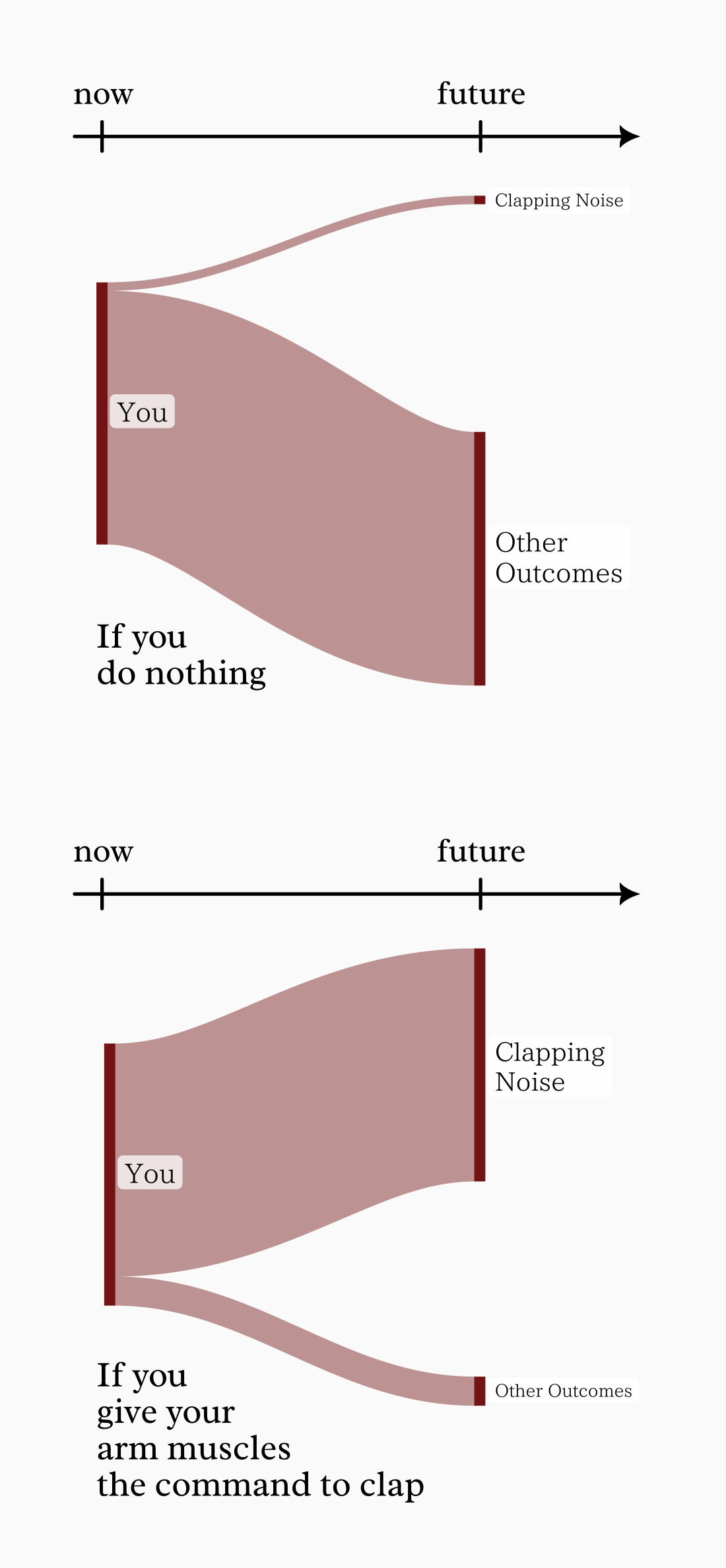

To begin understanding how purpose works, look again at the first example I shared of a control mechanism involving a person.

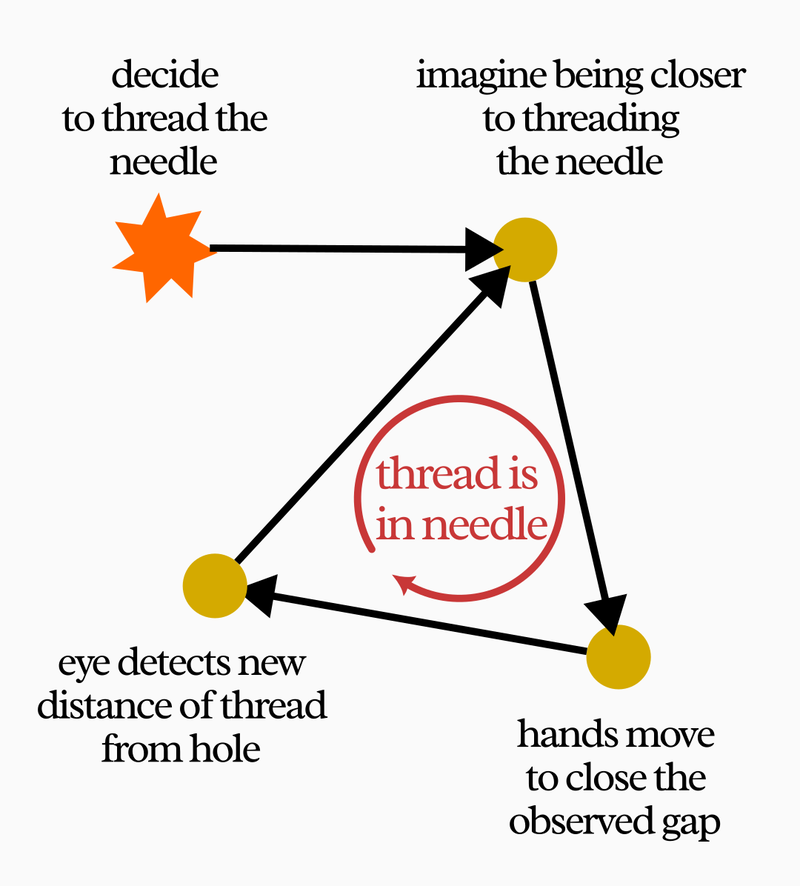

Sorry. I cheated a little when I made this diagram. It showed that a feedback loop was involved, and in this sense it did its job. But, for the sake of simplicity, I glossed over the most important aspect of human-driven control: the “want” part of the definition above. In order for the threading of a needle to happen, it must begin with someone’s intention to thread the needle in the first place!

This is a more comprehensive version of the loop:

And more in general, covering all possible control loops:

Let’s break this down into elementary pieces.

The Intent

Unlike the self-smoothing pebble and the tidily layered stars, those human actions don’t happen due to random forces. You need to first imagine them—that is, simulate a possible state of the world in your mind, one that you want to become reality—and only then can you kick off the loop that will take you there. Whether the desired state is an increase in sales, a sense of accomplishment, or simply ice cream in your mouth, you have to know about it and imagine it at least vaguely to even hope to get it.

The key point is that the simulated reality in your mind is something that is unlikely to happen on its own, without your intervention. The needle won’t thread itself [citation needed]. Your index finger won’t randomly scratch your nose without you imagining, somewhere more or less hidden in your consciousness, “I sure would like my nose to be scratched now”.

If something would happen reliably even without you trying to make it happen, then you wouldn’t need to imagine it beforehand. You would just take it for granted. For example, you don’t need to imagine “I want my room to be filled with breathable air 10 minutes from now”, nor do you need to start a control loop to make it happen, because that is 100% going to happen anyway (unless you’re in a spaceship’s airlock, I guess).

Control is for the things that are improbable on their own, recursion is how you make them probable, and intent is how you start the control.

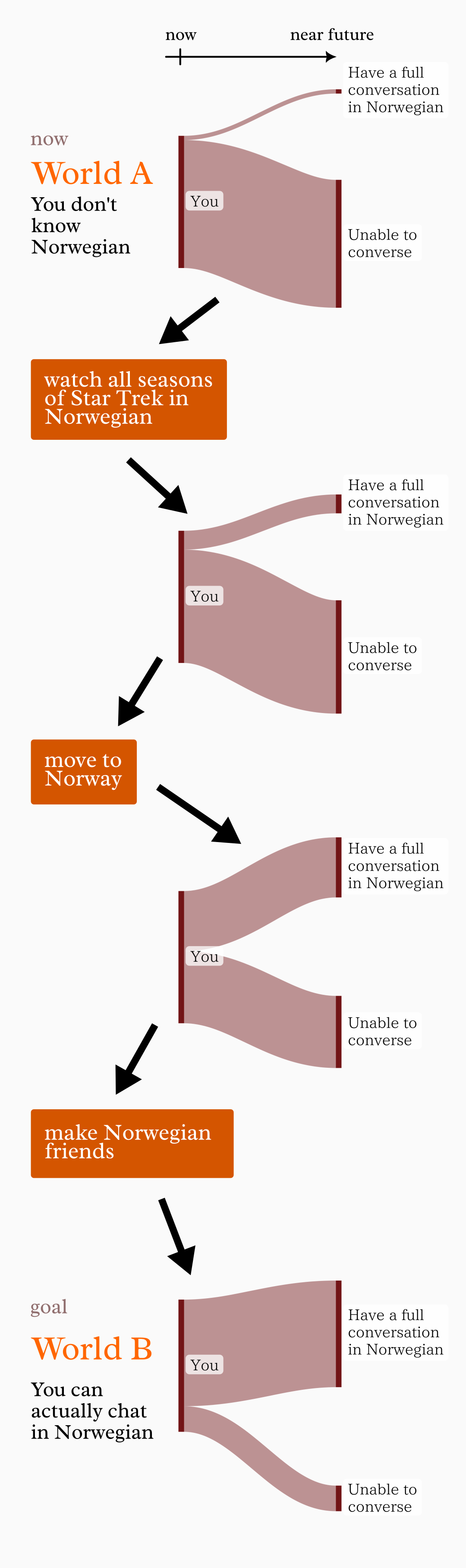

Here’s the Plan

Now that you have a desired state in your mind, you need to change the world so that it reaches that state. In other words, you need to increase the chances of that state happening from its current low probability to a probability that is close enough to 100% as you can manage. You need to turn that imagined state into a Water Lily.

You start with a gap between what the real world is like now (call it World A), and what the desired world is like in your mind (World B). Then you ask yourself: what needs to happen in order for World B to become very probable? What things around me need to be arranged differently, what obstacles need to be removed?

If World B is “me with a less-itchy nose”, or “me with eyes closed”, the answer to those questions is simple. You only need to recruit a few muscles, i.e. something you can usually trigger easily with a single thought. An instant, and the goal achieved. Even in such simple processes your body triggers many feedback loops, but they come to you almost for free thanks to millions of years of evolution. Movement of your own body—within its specific and personal limits—is the one thing you can usually take for granted.

Many of our goals are harder than that, though. A single muscular action can’t win you a degree or eliminate world poverty. Even a very mundane and achievable World B like “me, but less thirsty” usually needs more than a single twitch of a limb.

What do you do then? You use your brain’s simulation abilities to imagine a sequence of intermediate worlds, each a little bit closer to World B, your goal. In other words, you break down the actions needed to get what you want into smaller goals, each increasing the probability of the next goal via control loops, until you can expect to reach the goal state. This is what we call a plan.

Even when you don’t realize it, a new plan can only be created backwards: you start by imagining the final goal state, then you look for a neighboring world state, one that is very similar to it except for one realistic obstacle added in. When your purpose is to relieve your thirst, that neighboring state might be “me with a glass full of water at my lips”: that state would not be the same as relieving your thirst, but it is only one easy step removed from it—just a (controlled) twist of your wrist.

The newly found neighboring state becomes a new goal in itself, what we might call a “sub-goal”. You don’t care about putting a glass of water to your lips for its own sake, but it’s a good milestone to aim for, en route to your final goal.

Of course, the next question is how to achieve that sub-goal. You repeat the same process, imagine another neighboring state with an added obstacle (“standing next to a glass full of water”) and make another sub-goal out of it. Keep repeating this process, build a long-enough chain of neighboring states, and you might eventually get to a state that is neighboring your current situation, World A. If you succeeded, you now have a plan—a sequence of recursive increases in the probability of your desired world state happening.

More difficult goals will require more steps in their plans, and you may have to further break down your sub-goals into sub-sub-goals, going as deep as necessary.

Planning Caveats

This is, of course, a gross simplification. For one thing (as we’ll see) plans aren’t always so neat and linear. Another thing to keep in mind is that there is often no single way to divide the path from World A to World B into a progression of steps. Any purpose may be fulfilled in several different ways, and even within a single plan one might highlight different states as sub-goals—“hand on fridge’s door” is just as valid as “standing in front of open fridge” as sub-goal for the purpose of being “less thirsty”. Planning is an art more than it is a science. What matters is that you simulate intermediate states in your mind, then you execute by focusing on one sub-goal at a time.

Finally, most plans are doubly recursive. Recursion is certainly at play during the execution of every sub-step, but often you need to implement an additional feedback loop in the planning itself. Your ability to predict future states might be limited, the situation may change unexpectedly, or you may simply fail at one of the sub-goals, making your initial plan moot. In these cases you’re forced to observe the new reality—World A v2—and to forge a new plan in your head. This could be a small correction to your previous plan, or a complete overhaul.

The Key Difference

Now we have a new way to explain purpose very generally:

Purpose is a simulated Water Lily that is part of a plan.

It’s not just any Water Lily; it is one that you imagine ahead of time, and by intending to achieve it, you produce some form of plan to apply control (feedback) so that it becomes a real Water Lily. Purpose is always a figment, and it ceases to exist the moment the Water Lily is realized and your intent fulfilled.

Definitions are only as good as the power of distinction that they bestow. What is special about this kind of Water Lily we call purpose?

The special part is not the presence of feedback loops, nor is it the gradual convergence towards a specific outcome. That happens in any case, and Water Lilies of any kind, including when they arise randomly, can be very complex.

What is different in purpose as opposed to other kinds of Water Lilies is whether or not the order in which things happen matters.

In a non-purposeful Water Lily (I’ll call them Wild Water Lilies from now on), it doesn’t matter which step in its feedback loops kicked off the recursive action. Whether the first air current that formed a tornado was pointing south or northeast—whether it was a butterfly’s wing-flap or someone’s sneeze—has absolutely no bearing on what comes later. Only the fact that strong winds are strengthening each other in a deadly loop is important: all elements participating in the loop are equal peers.

Similarly, it makes no sense to try discovering the shape of the “first” rock fragment that seeded a planet’s formation, because many such rocks and dust clouds attracted each other at the same time. And when a magnetic levitation train hovers at a constant height above its magnetic tracks, it is useless to argue whether it is the tracks or the train itself that “starts” the levitation.

The moment a feedback loop connects, it transcends the specifics of its initial conditions. Each part becomes the cause of all the others—and, of course, of its own future changes. Cause and effect cease to make sense. Something new and whole is happening, and the only direction of change is not among the elements of the loop, but of the loop itself towards its Water Lilies. It continues as long as it does with no way to mark a point of arrival.

The snow crystals in a rolling snowball feed their contributions to each other and trigger increasingly rare effects: a large amount of snow quickly moving downhill, a groove on the snowball’s wake, the round shape of the snowball itself. All of these things can be considered Water Lilies, and there is no “goal state” in the loop itself. Every snowball comes to an end against an obstacle or at the bottom of the hill, but it doesn’t matter, because it had no plan and thus couldn’t fail.

Control loops are the exception. Physically, they work exactly like any other feedback mechanism, except that they are always triggered by someone’s intent. They don’t just happen: they’re made to happen. This distinction breaks the symmetry, so that only in purposeful loops do the beginning (intent) and end (desired Water Lily) actually matter.

Part 3: Purpose Paths and Purpose Networks

Plans Are Paths

The problem with a word like “purpose” is that it feels so fuzzy and abstract, even though it’s about something very practical. Let us try to visualize it, and see where that takes us.

I’ve thought long and hard about this, and reached the tentative conclusion that the most representative, ubiquitous kind of purpose is “literally getting from A to B”. As in: you’re in a big city, you want to catch a train at Station A and arrive, as quickly and conveniently as possible, at Station B. A nice and easy purpose!

“You being at Station B within an hour” is the goal, the imagined state of the world that you hope to turn into reality. It’s not likely to happen unless you actively try to make it the Water Lily of several controlled feedback loops. Even jumping on a random train and changing trains randomly a few times isn’t going to work. You need to look at a train map, mentally survey which lines arrive at Station B, and perhaps retrace your imaginary steps a few times in search of viable connections. Gradually, you construct a feasible, uninterrupted path that connects the two stations.

That promising path is your plan. All plans work like this: getting a glass of water also required you to make a mental simulation, but in that case using milestones like “standing up” and “holding the glass” instead of a sequence of locations. The intermediate stations you change trains at are the sub-goals in your plan, all subordinate to Station B and only important because they make your probability of reaching Station B gradually higher.

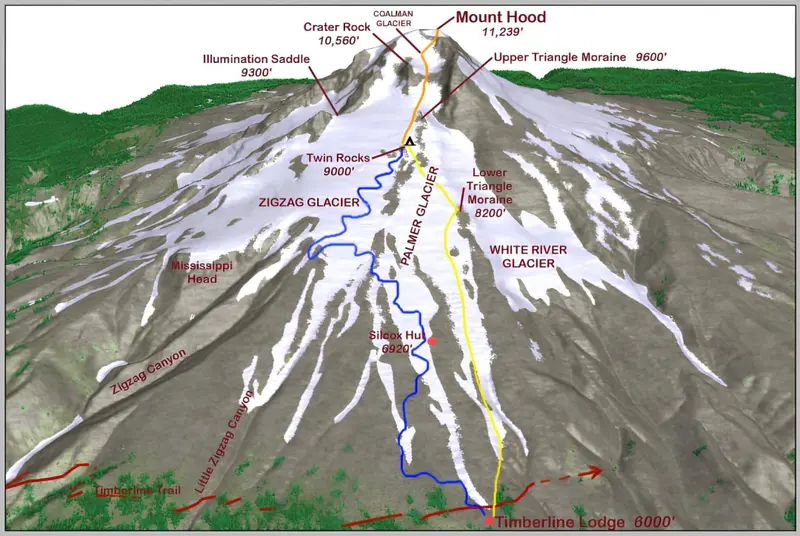

An even better example is something like this:

The goal is to get to the top of the mountain. This metaphor makes it clearer that the path is made more difficult by obstacles and geographical features. It’s never straight and easy, but winding from one base station to the next, just like any other plan. We’ll use this as inspiration to draw simple “purpose diagrams”.

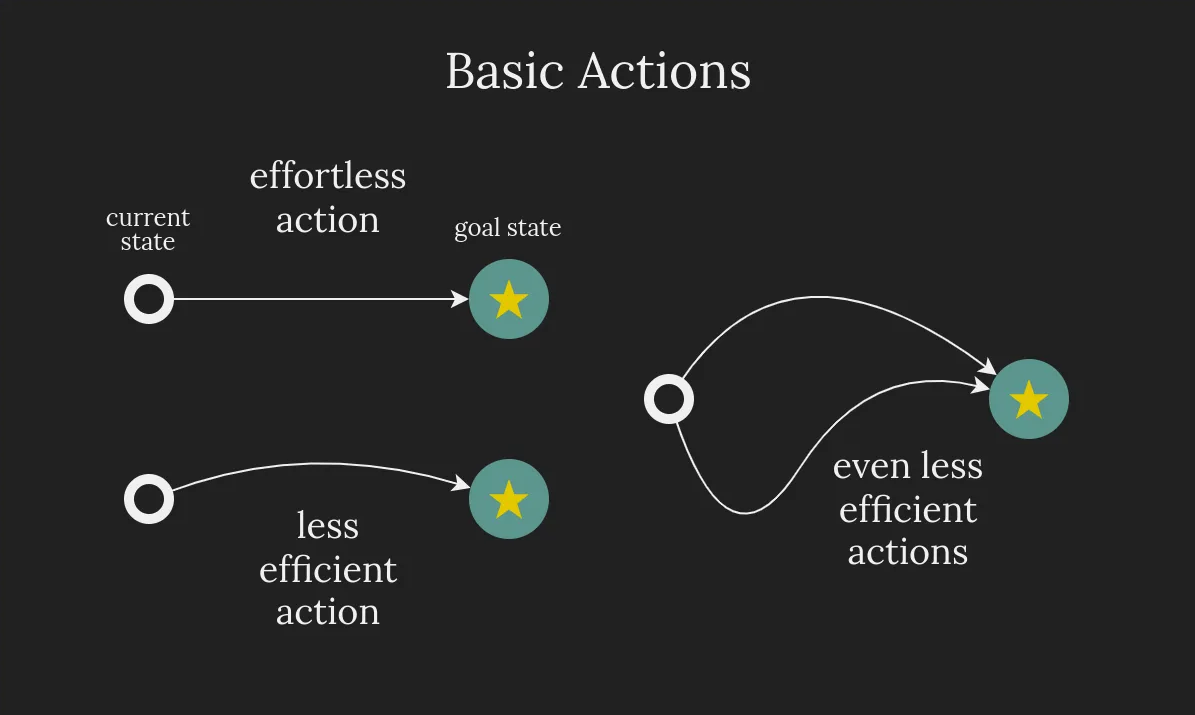

To keep the diagrams really simple, we’ll draw the paths but not the “mountains”—just keep in mind that there are impervious “reality mountains” all around.

Let’s also say that a straight line is the easiest and most efficient kind of action possible, like using a cable car. Examples of something you might draw as a straight line would be “blinking your eyes” or “saying a word”, but anything harder than that will be a curved line: longer and thus more effortful, like climbing around crags and crevices.

An example of a less efficient action might be pushing a table aside in order to make room for a new sofa, or walking for a while: more effort or time is needed than a one-time muscular action, but still simple enough. We don’t need to be precise here—the curvature is only a reminder that the steps of a plan aren’t always equally easy.

Aside: Arrows = Loops 🔁

I chose to use arrows for these diagrams, to lean into the metaphor of going places, but you should always keep in mind that behind every arrow is not a linear cause-and-effect process, but a feedback loop between senses, mind, muscles, and the part of the world the plan is trying to modify to match an imagined goal.

It’s like when you’re walking up a mountain path, where you have to keep a careful eye out for obstacles and adjust your every step to the local conditions. It is not apparent from these simplified drawings, but plans are always about control loops.

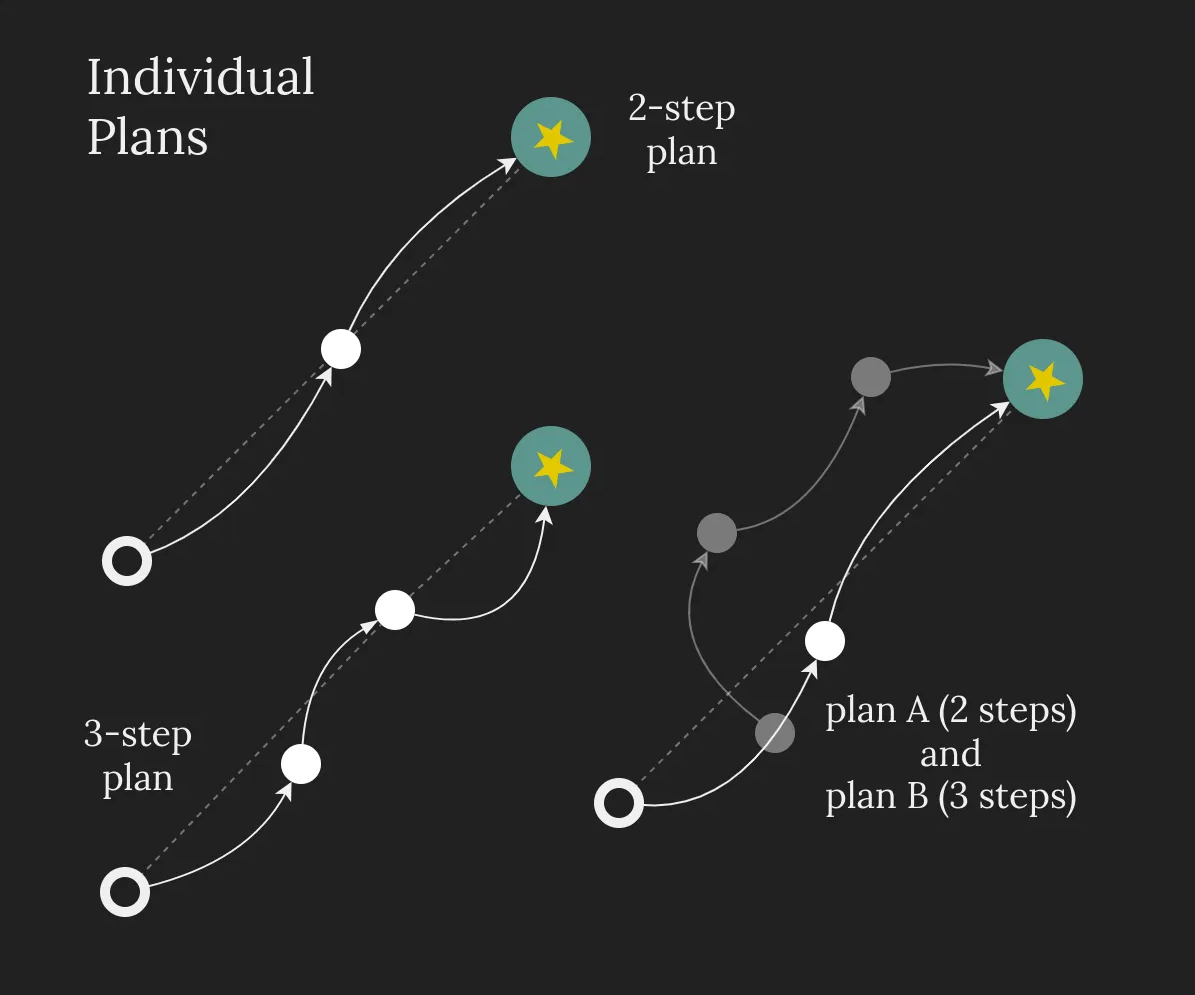

Now, since plans usually involve multiple steps, they tend to look more like this:

This is like the waystations on the mountain trail, a couple of images up. First you might plan to get to Silcox Hut and take a break, then go take a nice look at Zigzag glacier, then stop for the night at Twin Rocks camp, and so on. (Don’t take my advice, though, I’ve never actually climbed Mt. Hood!)

Goals form chains connecting the Now to the final goal. Different plans will lead to different sub-goals, and thus to different paths to the same destination.

As we’ve seen, a plan doesn’t pop up in your head fully formed in all of its details. You go by degrees, beginning with a very rough high-level plan and gradually thinking about the finer plans necessary to achieve the intermediate goals.

These diagrams are useful to understand the structure of a plan at a glance, and we’ll use them more below, but they can get messy if you try to add a label for each little dot on there. Another way to represent a plan with its clear hierarchy of goals, sub-goals, and sub-sub-goals is with… a simple bullet list.

Here are some bullet-list examples of concrete plans you can explore by selecting the tab you want.

Goal: Quenching Thirst

- Go to kitchen

- Stand up from sofa

- Walk to kitchen entrance

- Enter kitchen

- Get an empty glass

- Walk to cupboard

- Open cupboard door

- Choose a glass

- Take glass out of cupboard

- Close cupboard door

- Walk to table

- Place empty glass on table

- Get water bottle

- Walk to fridge

- Open fridge door

- Find water bottle

- Take water bottle out of fridge

- Close fridge door

- Walk to table

- Fill glass with water

- Remove bottle’s cap

- Pour water into empty glass

- Drink water

- Put water bottle down on table

- Pick up water-filled glass

- Drink from glass

Goal: Getting a Haircut

-

Go to shop

- Get in car

- Take keys

- Open house door

- Walk to parking lot

- Unlock car

- Open car’s door

- Sit in driver’s seat

- Close car’s door

- Drive to the barber shop

- Start car’s engine

- Back out of home parking lot

- (Abridged: several steps of driving through intermediate locations)

- Drive into barber’s parking lot

- Park car

- Stop car’s engine

- Exit car

- Open car’s door

- Step out of car

- Close car’s door

- Lock car

- Enter barber shop

- Walk to shop’s entrance

- Enter shop’s door

- Get in car

-

Get haircut

-

Wait for own turn

-

Sit on barber chair

- Locate specified barber chair

- Walk to specified chair

- Sit down

-

Allow barber to do their job

- Explain desired haircut

- Sit still

- Wait for operation to be completed

-

Goal: Doing the Laundry

- Prepare laundry

- Gather dirty clothes

- Walk to bedroom

- Collect dirty clothes from hamper

- Walk to bathroom

- Collect dirty towels

- Carry all items to laundry room

- Sort clothes

- Separate whites from colors

- Check pockets for items

- Remove any items found

- Load washing machine

- Open washing machine lid

- Place sorted clothes inside drum

- Close washing machine lid

- Gather dirty clothes

- Wash clothes

- Add detergent

- Open detergent container

- Measure appropriate amount

- Pour detergent into dispenser

- Close detergent container

- Set wash cycle

- Turn dial to appropriate setting

- Select water temperature

- Adjust load size setting

- Execute wash cycle

- Press start button

- Wait for cycle to complete

- Add detergent

- Dry clothes

- Transfer clothes to dryer

- Open washing machine lid

- Remove wet clothes

- Open dryer door

- Place clothes in dryer drum

- Close dryer door

- Set dryer cycle

- Turn dial to appropriate heat setting

- Set timer

- Start dryer

- Press start button

- Wait for cycle to complete

- Transfer clothes to dryer

- Finish laundry

- Remove clothes from dryer

- Open dryer door

- Take out dried clothes

- Place in laundry basket

- Fold clothes

- Pick up each garment

- Fold according to type

- Stack folded items

- Put away clothes

- Carry folded clothes to bedroom

- Open dresser drawers

- Place items in appropriate locations

- Close dresser drawers

- Remove clothes from dryer

Goal: Going on a Family Trip to Lisbon

- Plan trip

- Choose travel dates

- Check family calendar

- Identify available dates

- Confirm dates with family members

- Book flights

- Search flight options online

- Compare prices and schedules

- Select preferred flights

- Enter passenger information

- Complete payment

- Save confirmation emails

- Book accommodation

- Research hotels in Lisbon

- Read reviews and compare prices

- Select preferred hotel

- Make reservation

- Save confirmation details

- Plan activities

- Research Lisbon attractions

- Create itinerary

- Book tickets for major attractions

- Make restaurant reservations

- Choose travel dates

- Prepare for travel

- Get travel documents ready

- Check passport expiration dates

- Gather all passports

- Make copies of important documents

- Store documents in travel folder

- Pack luggage

- Check weather forecast

- Lay out clothes for each day

- Pack clothes in suitcases

- Pack toiletries and medications

- Pack electronics and chargers

- Check airline baggage restrictions

- Prepare house

- Stop mail delivery

- Arrange pet care if needed

- Set lights on timers

- Lock all windows and doors

- Get travel documents ready

- Travel to Lisbon

- Go to airport

- Call taxi or arrange transport

- Load luggage into vehicle

- Travel to airport

- Arrive at departure terminal

- Check in for flight

- Find airline check-in counter

- Present passports and tickets

- Check baggage

- Receive boarding passes

- Board flight

- Go through security screening

- Find departure gate

- Wait for boarding announcement

- Present boarding passes

- Board aircraft

- Find assigned seats

- Store carry-on luggage

- Go to airport

- Arrive and settle in Lisbon

- Complete arrival procedures

- Exit aircraft

- Go through passport control

- Collect checked baggage

- Exit airport

- Get to hotel

- Find transportation to city center

- Travel to hotel location

- Enter hotel lobby

- Check into hotel

- Approach front desk

- Present identification and reservation

- Complete check-in process

- Receive room keys

- Go to assigned room

- Unpack essential items

- Complete arrival procedures

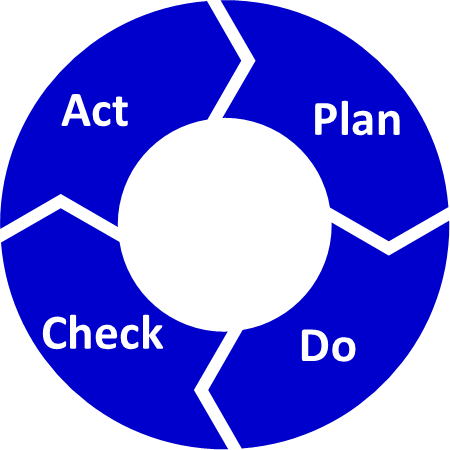

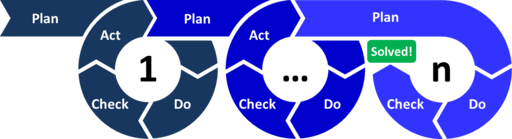

The fact that plans are made of chains of steps only means that there are many linked control loops like that at each level. Again, this idea is captured by common business frameworks like PDCA:

But surprises happen, and often the mental simulation used to make your initial plan turns out to have been faulty all along. Like a mountaineer who finds themself in an unexpected cul-de-sac, in these cases you have to go back to the (mental) path-finding stage, and it might well be that the new path and milestones you contrive this time are nothing like the ones you initially envisioned: back to base one.

With these new ways to visualize and think about plans in the toolbox, let’s leave our cozy climbing gym and briefly contemplate the veritable PURPOSE-HIMALAYAS that we call the Real World. Because purpose is very rarely as linear and straightforward as the pictures above may lead you to believe.

Plans Are Networks

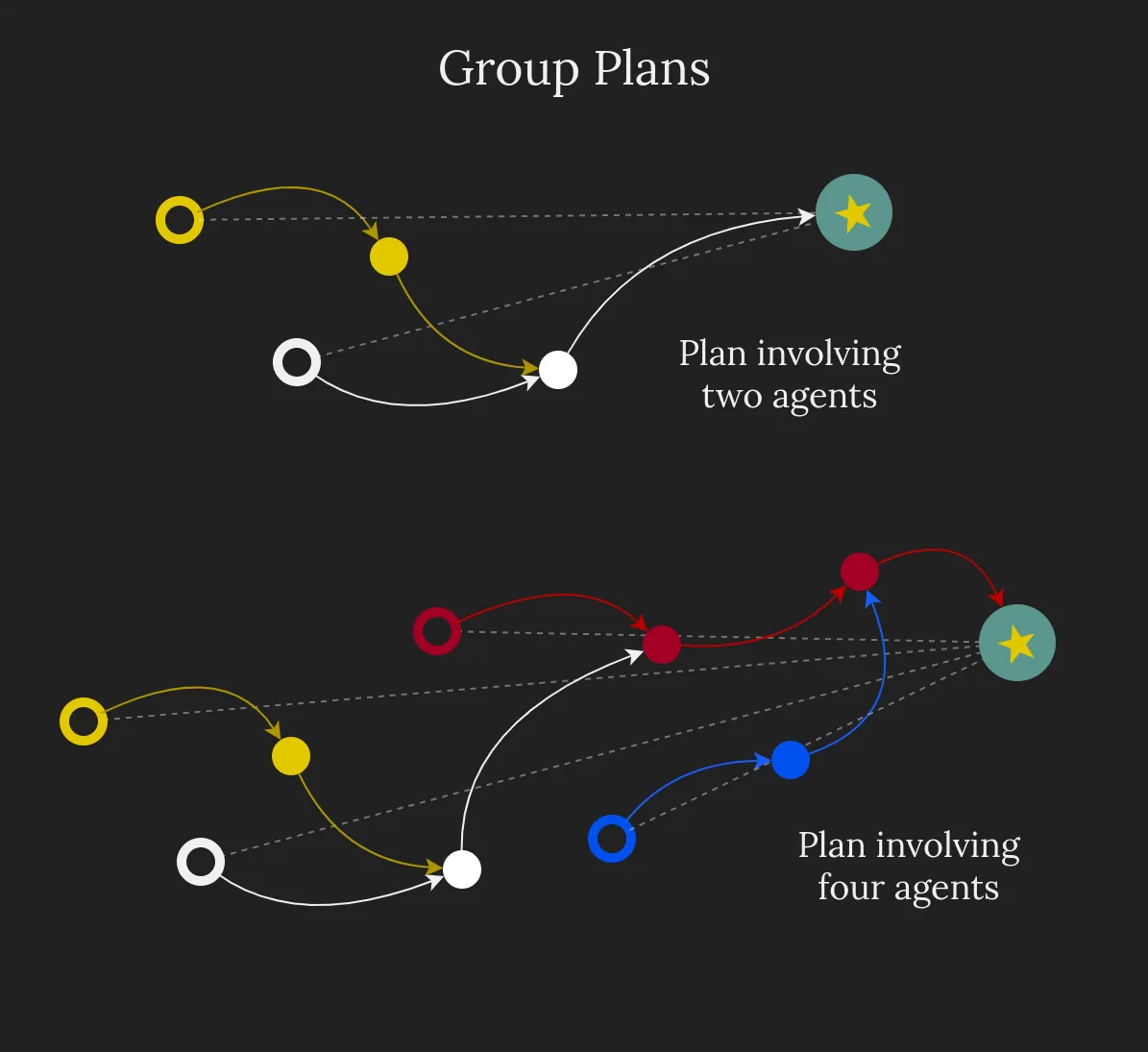

The thing is, no man is an island, and I’ve never heard of woman islands either. We work together, we dream together, and we make plans that involve many people at once. What do those plans look like? Something like this:

We devise plans that can be partially or completely executed in parallel. In the mountain-climbing metaphor, this is equivalent to receiving support during the climb on a difficult peak: sherpas joining you to guide you, other people climbing part of the way to stock and maintain the base stations, and so on. These are different plan paths meeting at certain milestones to make the final goal possible.

As an example from daily life, think about the goal of going to watch a movie with a friend: it’s not enough for you to show up at the entrance of the movie theater if your friend doesn’t do the same. The goal state isn’t “me watching the film together”, it’s “we…”. You have a shared goal, but you each have your own sub-plans that proceed separately until some point when you converge and begin acting together (the two-branch plan in the diagram above).

Another example with roughly the same level of simplicity might be eating a fish: your branch of the plan involves going to the fish seller and ordering (say) a Japanese pufferfish, and the seller’s branch, which began hours or days before you arrived, involved buying your pufferfish from the fisherman and preserving it until you arrived. After you pay—settling the bill is another sub-goal, the only one you and the seller need to do together in this case—you continue with your own linear plan of bringing the fish home, preparing it carefully, eating it, and probably calling an ambulance.

You can imagine any number of even more complex group plans. A team of people building a house have a grand shared plan, seeded by the architect but greatly expanded and refined by engineers, general contractors, project managers, construction managers, and others. This plan includes not only the phases of building (“note: the roof happens after we excavate”) but also the budgets and procurement schedules, the site logistics, the management of stocks of materials, the payment of wages, the safety measures. Trying to draw the purpose diagram of a plan like that would probably require thousands of branches meeting at hundreds of sub-sub-sub-sub-milestones.

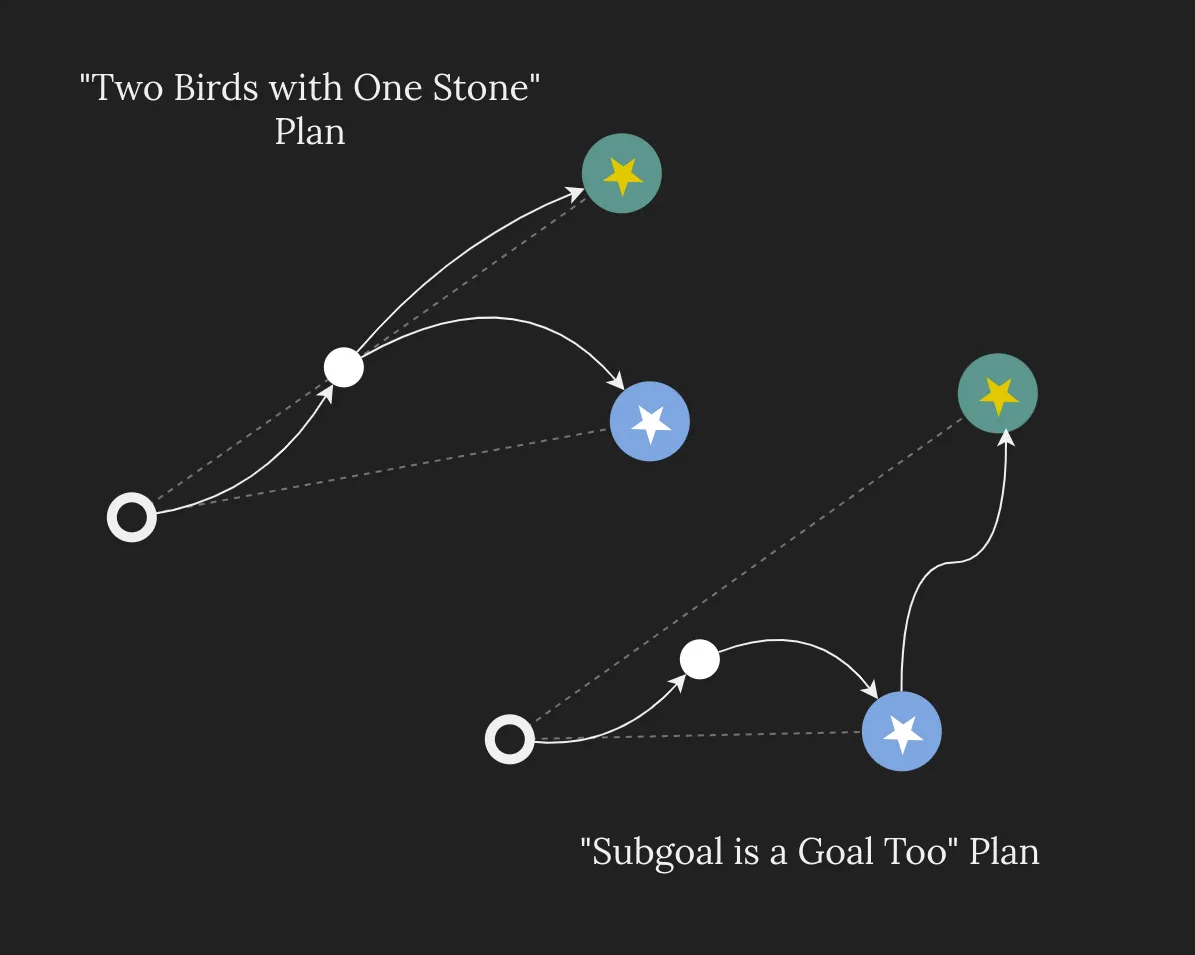

But purpose networks are not all about converging toward a single goal. If that were the case, how simple would life be, and how boring!

We all juggle many concurrent goals at any given time. You don’t just want to drink a cappuccino—you want to drink a cappuccino and have a chat with your friend the barman and not be late to your appointment with the lawyer. This is true at all levels of granularity, from the most immediate (get a breath outside and check your phone) to the lifelong pursuits (become an executive at your company and own a yacht).

In these cases—which is most cases—we try to come up with the best plans that let us achieve all of our goals. Often, these plans have some synergy with each other, and can share some of their steps for extra efficiency. Drinking a cup of coffee and chatting with the barman are two separate goals, but they are very much compatible: just buy the cappuccino at the cafe where your friend works. We might call these “two birds with one stone” plans. If you’re really lucky, one of your goals (e.g. learning Norwegian) is both a goal in itself—you would be happy to achieve it anyway—and a sub-goal towards a different goal (e.g. living in Oslo).

In all these cases, the idea is the same: some or all of the plan’s sub-steps help increase the probability of more than one of your goals at the same time. Neat!

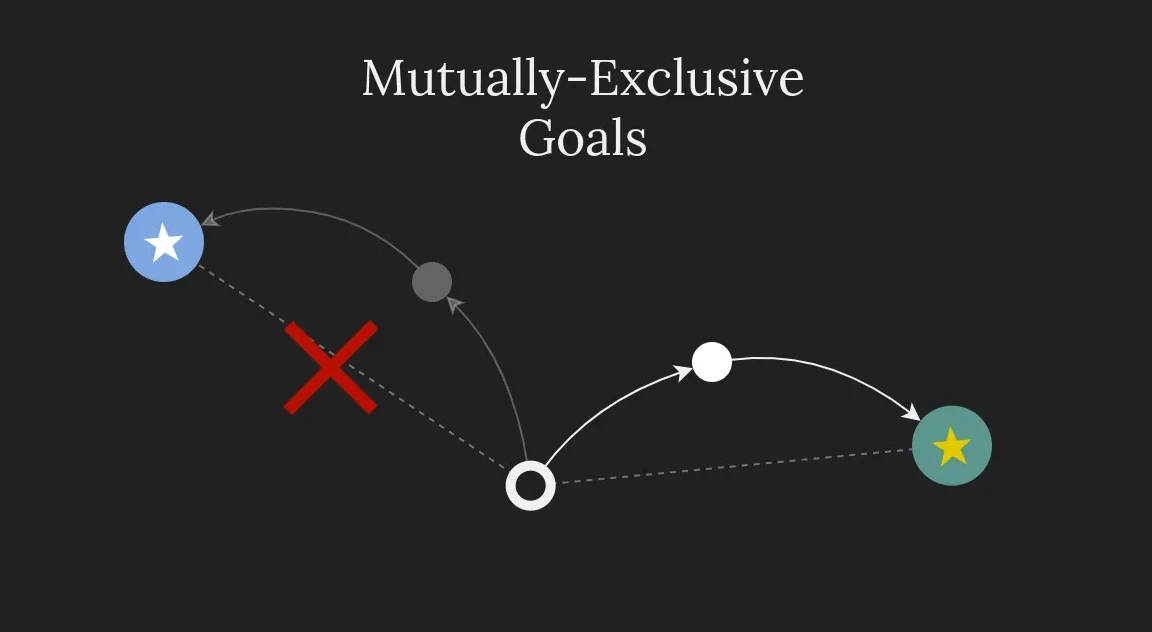

Needless to say, life is not always so obliging. Some goals seem to repel each other, and achieving one makes it much harder to achieve the other, not easier. This is what’s happening when you contemplate the goals “eating as many hamburgers as possible” and “staying fit”. In fact, people tend to be so keenly aware of cases like these, that I doubt I need to give any more examples.

If plans forking out to reach multiple goals are common for individuals, they are ubiquitous in groups of people. In house construction, for example, everyone in the project wants the house to get built, but do they all want it for the same reason? Most likely, each participant might have bigger goals of their own, for which the completion of the house is but a stepping stone—the architect might have a goal of winning an award, the project manager might want to get promoted, while an apprentice carpenter might simply want to pay the bills for the time being.

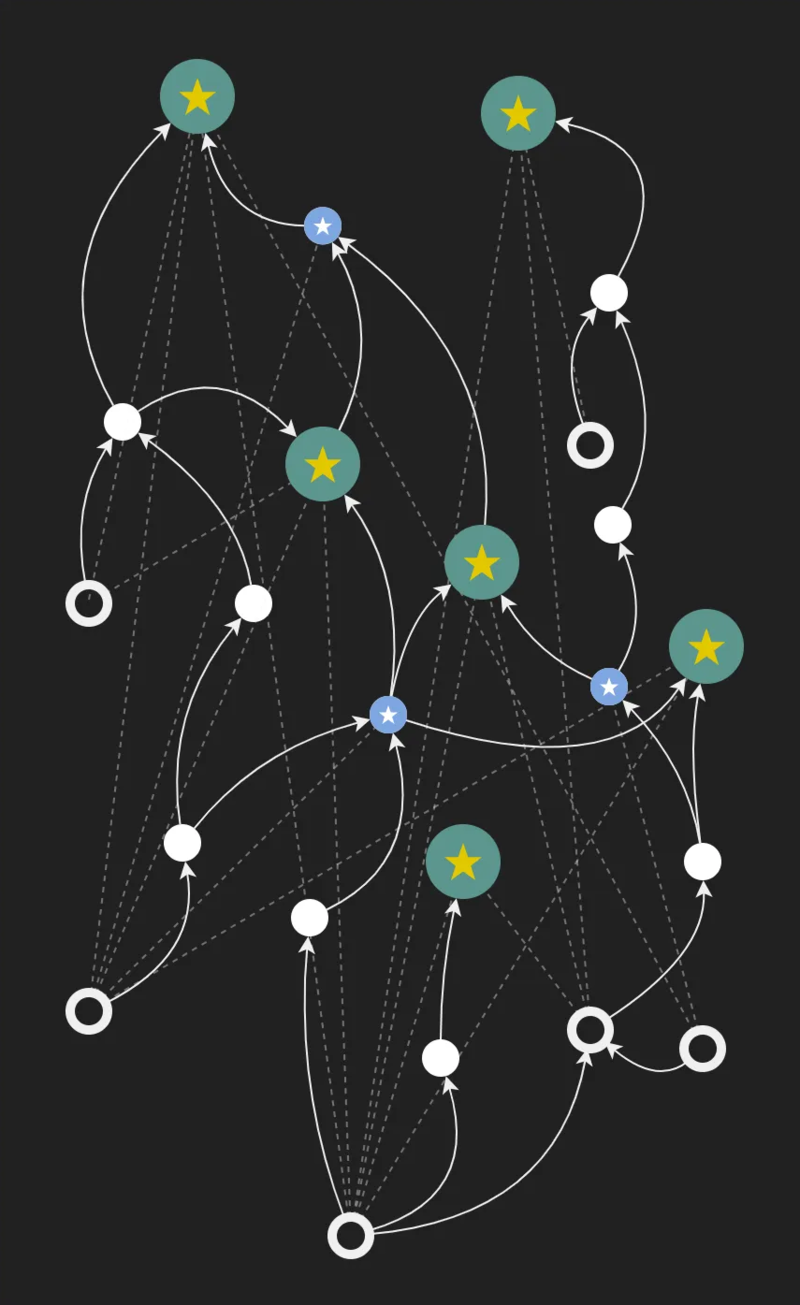

Then, putting it all together, a more accurate representation of real-life plans would look something like this:

We went from linear A-to-B schemes to intricate webs of intermingling control processes. Like the Ripple Universe itself, human and animal purposes are all joined in a single, enormous network of cooperation, sabotage, synergies, and mutual interference. It is another layer of interaction that allows for the mass-production of mind-boggingly sophisticated and unlikely new patterns.

Why Does Any of This Matter?

Given more time, there would be much more to say about purpose networks, more human situations that gain clarity through purpose diagrams, more arrows and dots to knot into garbles but… that’s enough for today.

This little tour in the mountainscapes of purpose was the shortest necessary to get one key insight, one nugget of intuition that will lead us on into the dark depths of the next section of our journey.

The takeaway is this: because, as we’ve seen, purpose always has a beginning and an end, it also naturally creates hierarchies of goals, sub-goals, and even smaller sub-goals. And when a hierarchy appears, it becomes necessary to keep track of all that. This boils down to three things one needs to know.

First, you need to know the start. It’s useful to know the starting point of a plan because it will tell you whose plan it is—a very useful piece of information.

Second, you need to know the end. The end point of a plan, of course, is nothing other than the goal itself. Knowing the end of your own plans is the only way you can hope to achieve them, and it’s a good idea to learn the goals of other people’s plans, too. Controlled action can turn some intricate and highly unlikely possibilities into reality: if you know where it’s headed, that gives an enormous boost to your predictive powers.

Last and most important, you need to understand the structure of the purpose hierarchies at play. A web of purposes is made to be traversed. It is what decides the relative importance of different actions and even the value we should assign to things.

In general, this is not true for non-intentional recursion. When no intentions exist, no objective ordering or limits can exist either, and all you need to know and understand are the forces and interactions at play. Wild Water Lilies can have no absolute or relative value. They just are.

Part 4: The Proper Place of Purpose

An ecosystem can’t possibly exist for a particular purpose.

— Hayao Miyazaki

The presence or absence of objective ends, beginnings, and hierarchies in those loops: this, then, is the critical distinction between mindless recursion and purposeful action—between Intentional and Wild Water Lilies.

| In General | With Intent |

|---|---|

| Wild Water Lily | Goal (Intended Water Lily) |

| Mindless recursion | Control process and replanning |

| Starting point does not matter | Starting point is key |

| End does not exist | End is the realization of the imagined goal |

| Events unfold by contingency | Events are controlled according to plans |

| No way to assign importance or value to events and elements | Hierarchies of goals, sub-goals and intersecting plans emerge necessarily |

Wild (i.e. mindless, non-intentional) recursion “just happens”. The resulting Water Lilies are whatever happens due to its feedback, with no inherent, defensible way to distinguish more or less “important” steps or hierarchies in their unfolding. As MIT professor John D. Sterman put it, “there are no side effects—only effects”. Everything that happens as a result of a recursive process, in general, is equally (un)important.

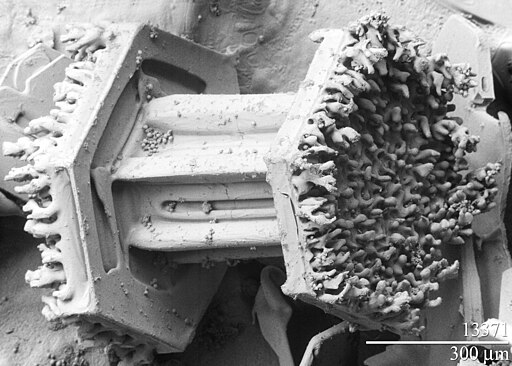

This needs unpacking. I will use a snowflake to do it, because snowflakes are cool and because they are famous for being rather mindless. These folks are Wild.

Similar but Different

Consider how beautiful this bunch of H2O is. So symmetrical, so perfect, and yet just as unique as you and me (darling). If you throw pellets of dough against each other at random, it’s very unlikely that you’ll end up with such a neat pattern of molecules. In the previous essay I showed that this is, in fact, another product of recursion. It feels natural, then, to ask, “how did the snowflake happen?”

Well, it’s more complicated than you think, involving several connected feedback loops, but if you’re curious, read one or more of them here:

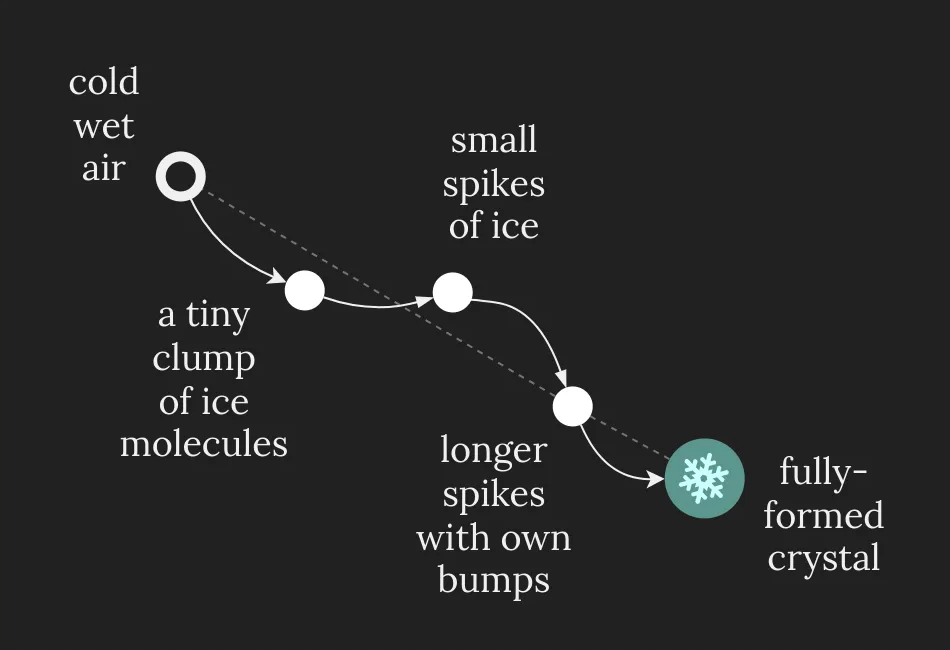

How a Snowflake Gets Spiky

The tiny point at the end of an arm collects water-vapor faster than the flat sides. More vapor lands on that point, so the point grows outward fastest. The longer it sticks out, the more vapor it collects—forming a branch instead of a boring flat plate.

Positive feedback (growth enhances conditions for more growth)

How the Snowflake Keeps Itself from Melting Its Own Progress

Each time a new ice layer forms, it releases a puff of heat. That warmth lingers like a stove’s pilot light for a few millionths of a second, creating conditions that temporarily prevent the next vapor molecule from depositing. Cooler air then flows in, the surface chills again, and another layer can form. The net effect is a quiet, rapid cycle of heat release and accumulation that keeps the whole flake growing steadily without ever halting its own growth.

Negative feedback (heat release temporarily inhibits further deposition)

How the Flake “Picks Winners”

If one branch gets a tiny head start, it begins absorbing the nearby water-vapor first. The air around that branch becomes poorer in vapor, so the other branches can’t grow as quickly. The already-advanced branch therefore keeps winning, becoming the longest finger on the snowflake.

Positive feedback (growth enhances conditions for more growth)

How the Flake Carves Itself Into Perfect Mirror-Flat Faces

Water molecules attach more easily at certain “steps”—ridge lines where molecules can bond snugly—and form less readily on the open flatlands in between. Each newly arrived molecule settles only on those ridges, raising fresh mini-stairs that act just like the old ones. Round after round of this tidy stacking keeps re-etching the same straight edges, so the originally random lump steadily sculpts itself into the familiar six-sided windowpane.

Self-organizing feedback (molecular preferences maintain geometric patterns)

It feels tempting to say, here, that the “finished” snowflake is the end product, and the steps necessary to build it—making it spiky, selecting which spikes grow longer, keeping it from re-melting, etc.—are all intermediate steps towards that end. You might attempt to draw a purpose diagram like this:

Just like a recipe, we have a sequence of control loops—an action plan, a story with a happy ending!

Alas, this is only a hallucination of the human mind. You, the observer, start with the implicit premise that what you call “fully-formed snowflake” is the important state, then you go backwards and reconstruct the processes that led up to it. With a retrospective mindset like that, of course it all looks like a build-up to the pretty shape.

But in truth there is no “finished” snowflake, only snowflakes in the state they happen to be when you catch them. In a hypothetical fall from an infinitely high cloud, under the right air conditions, a snowflake would keep growing without bounds with ever more complex shapes. Yet you have a sense that there is such a thing as a “finished” snowflake, and you subjectively enshrine that as the end of what comes before it.

But why shouldn’t you choose the first tiny bump on an irregular ice crystal as the “goal” of the process? Why not the water drop left after a snowflake melted? Whatever state you choose, at any point in space and time, has the same objective right to be defined as the “end product”—that is, no right at all.

This is a snowflake, too:

It has an unfamiliar shape, but it can happen when the conditions are just right. Is this the “goal” of the preceding steps, too? Why wasn’t the goal to make a more standard shape in this case? Who decides that?

Usually we pick the typically-sized, typically-shaped snowflake as the “end state” in our reflections only because we find them to be pretty, decorative, and mysterious. Everyone likes snow, and typical snowflakes have more recognizable shapes than most other natural phenomena, so it feels reasonable to give them a neat name like “snowflake” and to write lots of papers about them. That’s molecular discrimination, if you ask me. Crystalline favoritism!

This kind of arbitrary goal attribution is something we do all the time. It reminds me of the story of King Midas, the mythical king of Phrygia who had his most ardent wish granted by a god: the power to turn everything he touched into gold. After a brief period of ecstasy as he transmuted trees and flowers into precious metal, he realized that the same fate awaited all of his food and drinks, so that he couldn’t feed himself any more. When his daughter came to comfort him, he turned her into a golden statue, too. The gift was a curse in disguise.

We are all teleological King Midases—everything our thoughts touch immediately becomes imbued with our subjective purposes and interpretations. We graft our goals into the patterns around us, and suddenly we see beginnings and ends, hierarchies, plans, stories, and controlling forces in each of them. When all you have is a purpose, everything looks like control.

Is this wrong or silly? No, but also yes.

In one sense, it is not wrong to see Wild Water Lilies as if they were intentional, because their processes are very much like those of controlled plan execution: they involve recursion, and they make otherwise-rare patterns common. A snowflake is a Water Lily of its molecular feedback loops, just as a painting is a Water Lily of the painter’s mental and muscular loops. The parallels run deep.

But, in another sense, it is wrong to treat those things equally, because actual plans have a baggage of assumptions absent in more general Water Lilies: that plans need to be either aided or fought, for example, and that they have hierarchies of value.

The moment you think you see a plan, you become entangled with it. You become an actor in that purpose, whatever the role is that you assign yourself.

None of that makes sense for snowflakes, planets, or ecosystems. Purpose plays a fundamental role in much of our lives, but not in everything. It has its proper place in the reality. No more and no less.

Why Purposify the World?

As I mentioned in Part 1, the current best evolutionary explanation for promiscuous teleology is that it’s better to be safe than sorry, so to speak. For example, it’s less of a problem to incorrectly assume something mindless wants to kill you than to assume an actual killer is aimless.

But that explanation isn’t fully satisfactory to me. Why would detecting plans so greedily be useful? Let me speculate for a moment.

We function by predicting the future. Being able to guess someone’s (actual) goal ahead of time allows you to replicate the same mental simulation in your own head, and to find the most likely plans to achieve it. This is, in itself, an enormous boost in your predictive power: you can anticipate your enemies’ plans, intercept your quarry with your superior foresight, and improve your family’s chances of success by being there when they need you.

But reverse-engineering specific plans is the easy part. We are also busy trying to negotiate many intermingling plans at once belonging to groups of people.

This might be a major requirement and enabler of our sociality: navigating complex webs of nested purposes is difficult and important in social contexts, so having a keen eye for them would lead to better success, including more children to carry on your genes. Not to mention that people, when they coordinate their efforts in the right ways, can achieve things that would be impossible for separate individuals. Estimating each other’s intentions and aligning them into unified purposes is one of humanity’s biggest superpowers.

By extension, the same purpose-spotting skill could help us in our observations of many animals, like some mammals, birds, and certain fish, which some scientists believe might have analogous planning abilities.

The upshot is that we’ve become a keen, almost obsessive storytelling and story-loving species. Everything can be storified by a human brain, from series of events that actually had objective beginnings, ends, and nested plans to open-ended processes like people’s lives and crystal growths, where all that teleological structure is absent.

Sometimes this is not a problem, and all is good. Other times it is a painful mistake.

Owning Up to Our Errors

This rather extended analysis of purpose and of our double-edged tendencies would not be worth the while if it didn’t yield some practical wisdom. And, I think, the best wisdom comes not from knowing how to do things right, but from knowing all the ways to do them wrong. So here, at last, we can dissect our teleo-mistakes and make them easier to avoid.

The gist is this: we constantly underestimate how pervasive and fertile recursion is. But this simple issue manifests itself in two major forms: erring from too much purpose and erring from dismissing Wild Water Lilies.

Mistake 1: Erring from Too Much Purpose

It is usually safe to storify something—pretend it has a plan and purpose—when all you want to understand is the process that is happening. In these cases, having a true beginning, hierarchy, and end isn’t critical to the discussion. Here you’re not tempted to root for or against the success of that faux protagonist, so there is little harm in speaking in “intentional language”.

For example, when David Attenborough says that a water plant “clears the surface by wielding its bud like a club”, like in this excellent documentary, all his verbs are those you would normally use with an intelligent being.

The narrator’s implicit assumption is, “let’s imagine that the plant is conscious and that winning a battle against the other plants in the pond is its goal,” and you (the audience) play along with that. This approach is entertaining, even poetic, and it might actually help you remember this scientific fact.

The trouble only arises if you shift from what happens to why it happens—the supposed “goal” of the process.

Remember, from Part 1, that the question “why?” can have two very different meanings: it can mean how come? (a question about the preceding sequence of events), or it can mean what for? (a question about the intentions involved).

If someone asked “why does the plant want to win the battle?” the temptation is very strong to answer, “in order to survive.” Bad move! Now intention is a thing we need to handle and explain in some way. An answer like that is responding to the what for variant of “why”, a question that only makes sense when real, intentional plans are in place. It’s a slippery slope:

“If it does that in order to survive, why [what-for] does it want to survive?”

“Well, because it wants to pass on its genes to a new generation.”

“And why [what-for] does it want to pass on its genes?”

“…because it wants to continue the species.”

“Wait, really?”

The thought process moves farther and farther in the wrong direction, and it gets gradually more untenable. It’s easy to pretend that a plant “wants” to get plenty of sunlight, but it’s not so easy to believe that a single plant can possibly be thinking about the perpetuation of its whole species. I even know people who can’t do that with their species!

A what-for-why question applied where there is no actual plan is like driving on the wrong side of the road—possibly safe for a couple of seconds, less and less so the longer you keep going.

The only meaningful way to answer the initial question is in the how come sense of “why”. For example, the plant “wants” to win the battle in the pond “because in the past the more aggressive plants survived and reproduced more, so they took over the population.” As I wrote in my mini-essay about water lilies (lower-case this time) there is no script, no higher or external purpose in the life of a plant. It is self-sufficient, self-creating, blind beauty.

Replace “plant” with any other feedback-rich process—a beaver, a smooth pebble, a layered star—and the situation remains the same. How-come-why is how you can understand things. What-for-why, interesting though it sounds, is how you paint yourself into a corner.

Mistake 2: Erring from Dismissing Wild Water Lilies

Projecting purposes too eagerly onto the world is only half of the problem. We also tend to downplay the self-sustaining, self-organizing power of Wild Water Lilies. They happen all the time and, unfortunately, we humans can’t help triggering new ones with every action we take, like drunks dancing in a crystal shop.

This is actually the context of Sterman’s quote, which I now cite again in a longer form:

There are no side effects—only effects. Those we thought of in advance, the ones we like, we call the main, or intended, effects, and take credit for them. The ones we didn’t anticipate, the ones that came around and bit us in the rear—those are the ‘‘side effects’’.

— John D. Sterman

Although some of what you do intentionally every day is indeed planned and goal-oriented, the effects of your actions ripple out into the world, through objects and people and larger patterns, and often trigger and participate in new, unplanned feedback loops. This is how human action, despite all the best intentions, can create Water Lilies that no one wanted.

It gets particularly bad when groups of people get together and kick off large, unstoppable Water Lilies while being none the wiser. As usual, here are a few examples you can skim through until you’ve had enough:

Backfiring Traffic Bans

Mexico City banned cars one day weekly based on license plates to reduce pollution. Instead, wealthier residents bought second cars to circumvent restrictions, increasing total vehicles and emissions—the opposite of the intended outcome.

- Story: Driving Restriction and Air Quality in Mexico City, Resources

- Intended Goal: Combat the city’s air-pollution issues.

- Water Lily: Increase in number of cars because people “gamed the system” by purchasing second cars.

Australia’s Cane-Toad Holocaust

In 1935 Queensland sugar growers imported cane toads to eat beetles. The toads didn’t exterminate the beetles but did multiply without bounds, and now occupy over 1.2 million km², poisoning native predators and pushing species such as the northern quoll toward extinction.

- Story: Introduction of cane toads, National Museum of Australia

- Intended Goal: Control cane-destroying beetles.

- Water Lily: Continental-scale ecological crisis initiated by a positive feedback loop in which toads ignored beetles, bred explosively, poisoned predators, and left more ecological niches for further toad expansion.

U.S. Prohibition (18th Amendment)

The 18th Amendment (1919) slashed legal alcohol consumption, but enriched bootlegging syndicates so rapidly that prohibition-related arrests jumped 102 percent by decade’s end, while murder rates surged from 6.8 to 9.7 per 100,000. Al Capone alone at one point earned an estimated $100 million annually.

- Story: American organized crime of the 1920s, EBSCO

- Intended Goal: Cut alcohol consumption and social ills.

- Water Lily: Explosive enrichment and empowerment of organized crime, whose profits from illicit liquor re-invested in ever-larger smuggling networks, making underground supply more probable year after year.

Green Revolution High-Yield Crops

Norman Borlaug’s high-yield wheat and rice averted starvation for a billion people on the Indian subcontinent, yet those crops demanded substantially more irrigation. Today the Indo-Gangetic Plain’s groundwater table is dropping at rates of 30-150 cm per year depending on location—with some of the most intensively cultivated regions experiencing declines exceeding 1 meter annually—threatening the food security the Green Revolution was meant to secure.

- Story: India’s groundwater crisis, fueled by intense pumping, needs urgent management, Mongabay

- Intended Goal: Prevent famine via higher food output.

- Water Lily: Intense and sustained depletion of the underground water table.

And here we reach the bottom of the rabbit hole: the source of many of the biggest problems of humanity stems from this refusal to respect Wild Water Lilies. I’m pretty sure it is this kind of “side effects” that prompted cybernetician Stafford Beer to famously claim that the purpose of a system is what it does (a.k.a. POSIWID):

According to the cybernetician, the purpose of a system is what it does. This is a basic dictum. It stands for bald fact, which makes a better starting point in seeking understanding than the familiar attributions of good intention, prejudices about expectations, moral judgment, or sheer ignorance of circumstances.

— Stafford Beer, speaking at the University of Valladolid in 2001.

His wording can be misleading, but what he means with POSIWID is this: don’t pretend that those undesirable things like worse car pollution and extinct species are not your fault just because they were not part of your plan. Your alcohol prohibition law has decreased legal alcohol sales and gave us Al Capone, and no one cares that only the former was “intended”. There are no side effects.

The system you created maybe does the things you want it to do, and it almost surely does a bunch of other things, too—some good, some bad. You can’t separate them. They are all Water Lilies, whether you control them or not.

The temptation is to dismiss those you don’t control, and this is the mistake: if anything, the ones you don’t control need more of your attention, not less. If unsavory “side effects” bother you, study all the loops involved, understand how they work, and come up with a better plan. Dude.

Hunger, poverty, environmental degradation, economic instability, unemployment, chronic disease, drug addiction, and war, for example, persist in spite of the analytical ability and technical brilliance that have been directed toward eradicating them. No one deliberately creates those problems, no one wants them to persist, but they persist nonetheless. That is because they are intrinsically systems problems—undesirable behaviors characteristic of the system structures that produce them

— Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Donella Meadows

Surveying the Bottom (Line)

Thinking errors like superstition, creationism, holy wars, and many of the obstacles to scientific progress—the ills and woes I mentioned in Part 1—are due to the belief that highly improbable and complex things cannot possibly arise by chance, and that such things must always begin with single causes and proceed with unidirectional sequences of cause and effect until they reach predetermined ends.

No one is completely immune to this kind of bias, because it seems to be built into the way the human brain works. We can’t help surrounding ourselves with the deceptive gold of purposefulness. Even highly-educated, reasonable people—including some scientists who presume that it is not even necessary to think about purpose—are prone to downplaying the scope and power of Wild Water Lilies.

When something complex puzzles us, we scramble to build stories to explain why it had to happen that way. When we break things we didn’t mean to break, we try to sweep the fact under the rug of “side effects” and “unintended consequences.”

Over and over, we forget

- that recursion is behind both purposeful action and purpose-less feedback loops,

- that recursion is much more common than anyone thinks, and

- that purpose is much less common than anyone thinks.

Only when you internalize these facts can you begin to attribute purpose to its proper place and role. 💠

The overall conclusions to this series are in the fourth essay, Carving Nature at Your Joints.

📬 Subscribe to the Plankton Valhalla newsletter

Notes

- Cover picture: photo by Arno Senoner, Unsplash

- Edit (December 19, 2025): Updated to reflect that this is now a four-part series, and added link to the fourth essay.