This is the first of four connected essays about some very fundamental things we get wrong without even realizing it. This first one returns to something I mentioned before, like BAEB and the Universal Network, but tries to drive the problem home: we’re able to use words for things, but it’s not so obvious why and how. The next two will be about the central role of feedback in how reality works, and about purpose, or the lack of it. The fourth will bring everything together.

- This essay

- Recursion, Tidy Stars, and Water Lilies

- Purpose from First Principles

- Carving Nature at Your Joints

Here we are, blissfully going about our lives, saying fancy things like “pass me the ketchup, please” and “the projections for our year-close budget ain’t pretty, folks,” and we’re satisfied with that. We never stop to ask ourselves whether we’re lucky we can call ketchup ketchup or whether the thing(s) we call “budget” will still exist three seconds from now. We kind of take those things for granted, as a self-evident truth about reality. But I want to show you that there is nothing self-evident about that. Being able to use language, or even just to live our lives without disintegrating immediately, is a mysterious privilege, not a given.

(If you were looking to inject a mild dose of existential dread into your day, followed by a redeeming miracle, you’re on the right page.)

First, I’ll explain how language is a very flimsy and arbitrary tool in itself. It’s deceptively simple—even children can use it—yet it’s built on a mountain of assumptions and contingencies that could really be chosen any other way. Second, I’ll try to make the point that, regardless of how precise or imprecise our language is, our habit of distinguishing things from one another doesn’t seem to be justified by how reality is built.

The most useful framing to see those things is what I call boundaries are in the eye of the beholder (BAEB).

Family Resemblances

None of the sounds we use to communicate with each other actually mean precisely anything, nor do they have to mean what they mean. The very act of assigning words to things means approximating and sacrificing truthfulness for convenience.

To begin with, human language gives you the impression of being able to categorize things with names. Our words feel so clear, so unambiguous in our daily lives, that any ambiguity or fuzziness becomes instinctively repulsive to us. We consult dictionaries, we ask for clarifications, we argue and get upset over the “real” meaning of “free will”, “justice”, “consciousness”, and “I’m fine”. Of course we know that words can’t be all that precise, that their meaning depends on context, and so on, but that’s still underestimating just how unreliable they are. Wittgenstein is on the front line ready to shake us out of our contentment:

Consider, for example, the activities that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, athletic games, and so on. What is common to them all? — Don’t say: “They must have something in common, or they would not be called ‘games’ ” — but look and see whether there is anything common to all. — For if you look at them, you won’t see something that is common to all, but similarities, affinities, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don’t think, but look! — Look, for example, at board-games, with their various affinities. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. — Are they all ‘entertaining’? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball-games, there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck, and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of singing and dancing games; here we have the element of entertainment, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way, can see how similarities crop up and disappear.

And the upshot of these considerations is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and crisscrossing: similarities in the large and in the small.

Wittgenstein calls this kind of loose similarities “family resemblance”. Words help us refer to things, but they usually lack a firm, universal essence that is not situational. Even so, you might rebuke, those family resemblances are still a family. Isn’t that a neat boundary, then? The Joneses don’t all look or act alike, but they are still all “Joneses”, after all.

Not really! That “complicated network of similarities” extends seamlessly beyond any barriers that our words try to put around them. The game of hide-and-seek resembles the police chasing criminals more than it resembles the game of chess; the game of rugby resembles two medieval armies clashing in battle more than it resembles Angry Birds; you might resemble your same-sex cousin—who has a different last name—more closely than your opposite-sex parent. Among all these loose links, we choose to group some under a given label—game, Jones—and not others, and it is a deliberate and arbitrary choice dictated by convenience. It’s preferable for humans to confuse a game of rugby with a game of American football than with an armed battle.

But what about more concrete words? It’s not too hard to believe that abstract concepts like “game” or “free will” are inherently fuzzy, but is that really the case also for things we can see and touch?

Where to Draw the Line?

A well-studied case are the label words we use for colors. In English we use six major color words: black, white, red, green, yellow, and blue. If you grew up speaking English (or a similar language) you might believe that there are indeed six or so distinguishable groups of colors, and that they are somehow properties of the world that we simply “read out” with our retinas, subject to some physiological limitations.

But that assumption is true only in part, because different human cultures label colors very differently. Some, like certain tribes in the Ivory Coast, only have three color words: black, white, and red. Other languages have four colors, and others still have five.

Field researchers interviewed native speakers of various languages with color terminology different from English. They showed them, one at a time and in random order, colored chips covering all of the following colors:

For each chip, they asked the participants to name the broad category of the color, and mapped those categories on the same grid. This is what they got (click to enlarge):

Notice how, for example, the nine or so hues on the chart that we English-speakers like to call “yellow” have been entirely subsumed into “red” in the Wobé and Bété languages of the Ivory Coast—yellow is red for them; our “sky blue” is a variation of “black” in those same cultures, of “yellow” by the Culina of South America, and of “green” by the other three tongues. And the same study found that, even among groups with the same number of color words, exactly where they draw the line between, say, “red” and “yellow” can vary a lot.

Colors are pretty visible but not very tangible. To dial up on the concreteness even more, take a look at this chart (click to enlarge):

For the Japanese, the Indonesians, and the Savosavo there is no distinction between what Anglophones call “foot” and “leg”. They’re just the same part of the body for those cultures, with a single word to refer to both together. The Lavukaleve speakers of the Solomon Islands don’t even need a distinction between arms and legs, they’re just limbs after all. Hands are just arm segments. But then they would laugh at the Indonesians, because obviously feet are separate from the rest!

We can’t even agree on what parts of our body merit to be treated as their own things.

This is part of a rich field of research in linguistics and psychology about how and whether different choices of categories like the above affect people’s thoughts and behavior. That’s a very interesting and important question to ask, but it’s not my point here.

My point is: the words we use define boundaries for things, giving us handy ways to tell things apart, but those boundaries are not universal. They’re not “in the world”, they’re practical shortcuts that exist only in human heads. If you look really closely, or if you look at the science, there is no strong reason to draw those lines one way or another. There is no defensible distinction between a mountain and a mountain range, or between a mountain range and the Earth’s crust, or between the Earth’s crust and the Earth. A mountain is the Earth, and calling it a “part” of it is a convention that suits us when we want to talk about going places, or studying cloud formations, and other very human goals. Some things seem to have more clear-cut separations between them, like the boundary between an egg’s shell and the air, but even then the demarcation is clear only under certain conditions (i.e. a certain range of temperatures and air pressures) and size scales (i.e. not at the atomic level or in terms of astronomical distances) and time scales (i.e. the egg stops existing as a distinguishable object after a while).

At this point it might sound like it’s all a problem of language, but that’s not the whole story. Even if assume that the words of your language are “good enough” and stop worrying about definitions, the question of how to draw the boundaries between things remains.

One Big Network

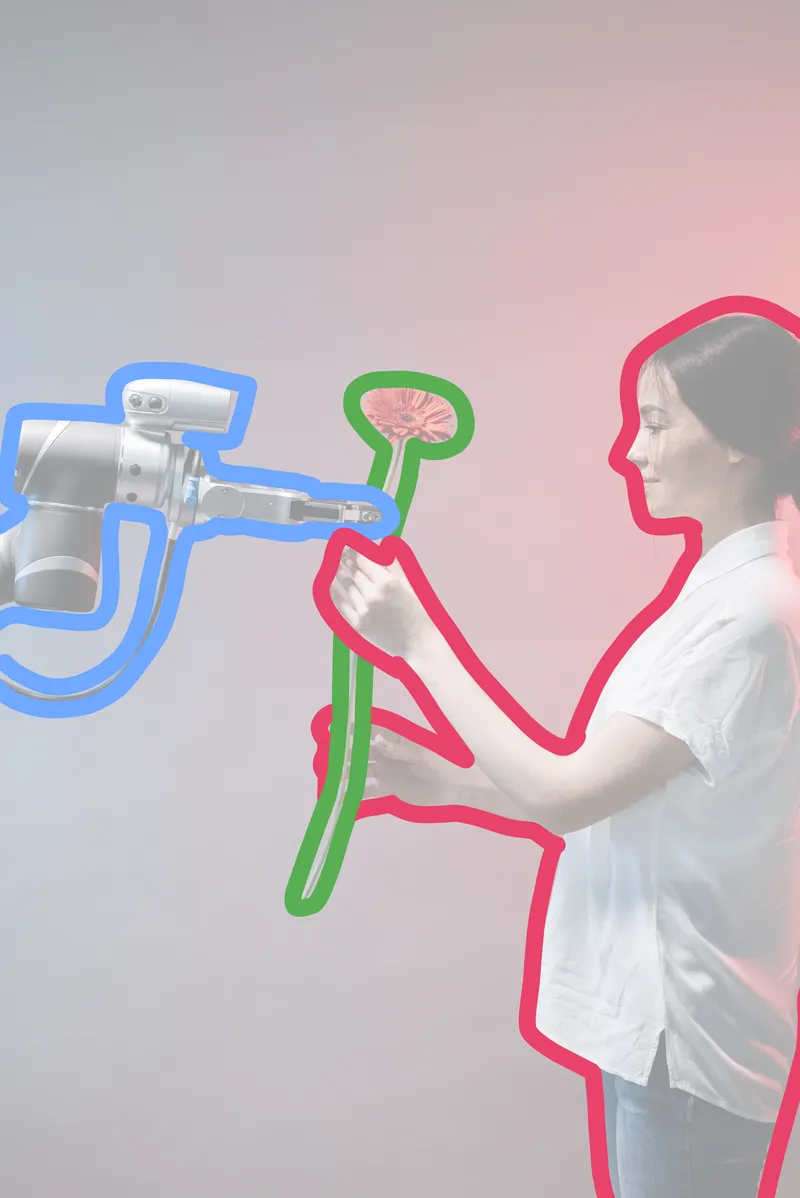

When you look at this stock photo, what do you see?

Most people would say something like “a robot arm giving a flower to a woman”. In other words, we tend to segment the picture more or less like this.

What we don’t generally do is describe the picture as “a woman touching a flower-carrying robot”…

…and definitely not as “a woman-touching-flower-carrying robot”.

We stubbornly see these things as three separate entities. But why three rather than two or one? Maybe you would answer that it’s because

- they each have different names (which we’ve temporarily decided are “good enough”) and

- they can exist and do various things independently: they have independent identities that are consistent over time.

Let’s take those arguments separately. First, the fact that they have their own names can’t be a reason to separate them in that unique manner. We could give a name to the whole subject of the picture, say, “gadorblk”, that from now on we can use to refer to woman-touching-flower-carrying robots whenever we see them. Not very useful, but not prohibited either. You hear of languages that have words for weirdly specific things like “the effect of sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees, creating a dappled pattern of light and shadow” (komorebi from Japanese) and “the roadlike reflection of moonlight on water” (mångata from Swedish). Why shouldn’t a language have a one-word noun for the content of this picture?

As for the idea that we need to count three entities because each of them—the robot, the flower, and the woman—independently has consistent properties (an “identity”) of its own, the question then arises: why not more than three, then? Why not count each panel and screw of the robot separately? You could distinguish each garment worn by the woman, and each petal of the flower, each with its own independent uses and properties. All these things are “attached” to each other by physical forces that, when you look closely, are the forces of atoms pushing or pulling at each other. Just like the atoms of the robot and of the woman’s hands are pushing and pulling at those of the flower.

We prefer to distinguish three objects in the picture because of convenience and habit, not because there is a deep, clear-cut distinction between them. Most of us see more meaning in this threefold separation than in any other. A robotics engineer, a botanist, or a fashion critic at work might find boundaries more meaningful.

Now we’ve gone beyond the realm of language, and are talking about the very nature of reality. The universe is one seamless, uninterrupted network of rippling and overlapping differences, and words merely project fuzzy boundaries that need only work well enough for our temporary and circumstantial needs. Even in very limited contexts where the words are relatively precise, our choice of terms to describe anything is arbitrary. In truth, everything is interacting, directly or indirectly, with everything else, and there is no obligatory, objective way to cut that web into separate entities. Nature has no “boundary-formation law” nor requirements for things to clump together and stay clumped long enough that we can give them names. In fact, the laws we have are all about energy transformations and waves and forces pushing and pulling stuff around: none are about keeping things still.

And yet, things do clump together, and they do remain still or stable, and we do have enough time to make up labels for them. The stability we take for granted—from that of the solid objects we see and touch to that of long-lasting processes like photosynthesis and life itself—seems to be some kind of freak accident. Stability comes as a side effect of mutability.

That, dear reader, is a very surprising thing. It’s like removing the familiar white cover (i.e. language) from your pillow to discover inside a frothing tangle of wriggling rainbow-flashing worms. “Have I really been sleeping on that all along?”

We might call this the “miracle of stillness”, and it’s a topic for the next essay. 💠

Notes

- Edit (December 19, 2025): Updated to reflect that this is now a four-part series.