Disclaimer: This is a repost of a Twitter thread I published recently, with all the stylistic quirks that the format entails.

Life creates itself, and self-creation is made of feedback loops.

In this thread I’m going to make that point using one of the most beautiful flowers as exemplar: the self-creation of the water lily 🪷

(This is not a thread about evolution. Evolution is itself an amazing castle of feedback loops, and it’s the process that made all I’m going to talk about possible. But plenty gets written about evolution already. Here we’re going to focus on a single, fragile seed of the water lily, an aquatic flower plant that grows all over the globe. We’ll grow and blossom with it.

We’re going deep, rather than wide, this time 🤿 )

But first, take a moment to look at it. Its beauty is so delicate, it feels almost impossible.

The question is, how does a little clump of cells at the bottom of a pond grow and develop into something so complex and pretty? And how can that happen over and over, under different conditions, in such a consistent way?

Spoiler: it’s not “just” genetic pre-programming.

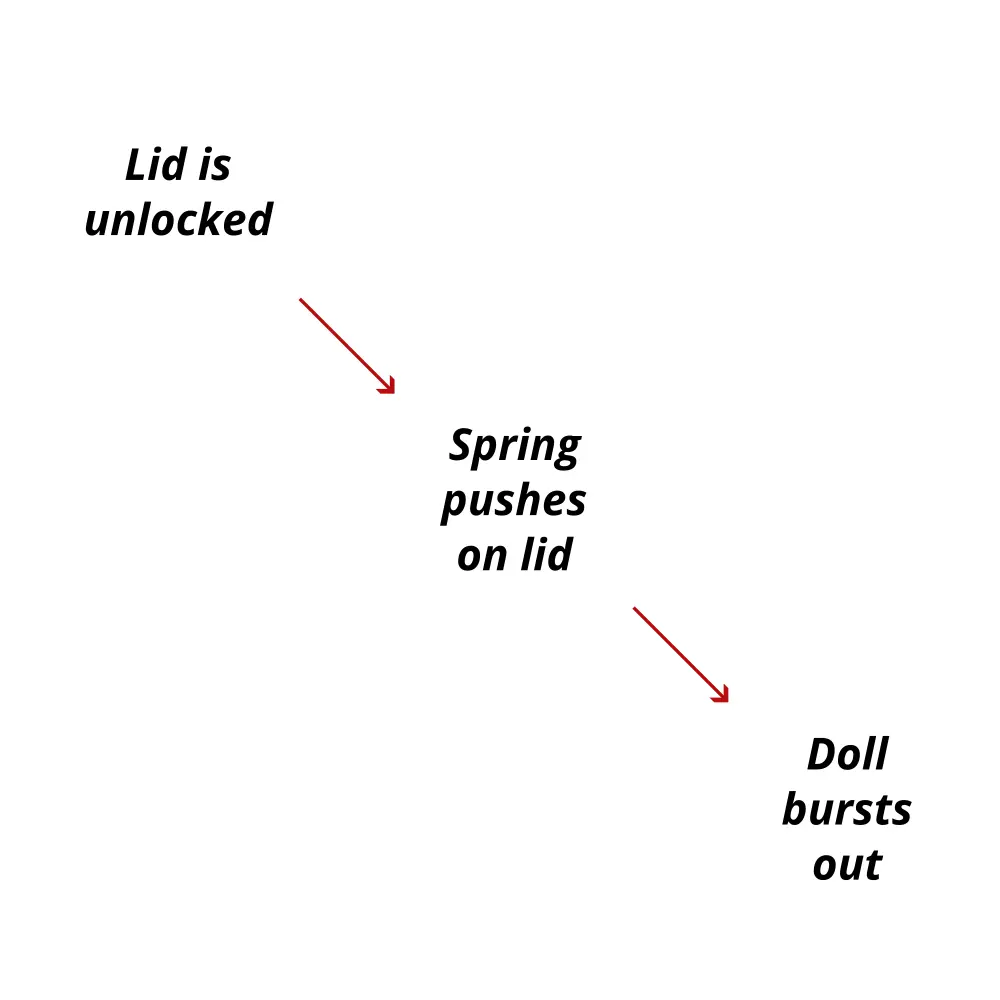

One might think that plant growth is fully dictated by a genetic blueprint, with each step unfolding according to a set of instructions, much like a jack-in-the-box: doing exactly the one thing it was designed to do, with only one way to do it.

Sure, you might say, every plant looks somewhat different from the others in the details, but that could be attributed to minor errors in the execution of the instructions, right?

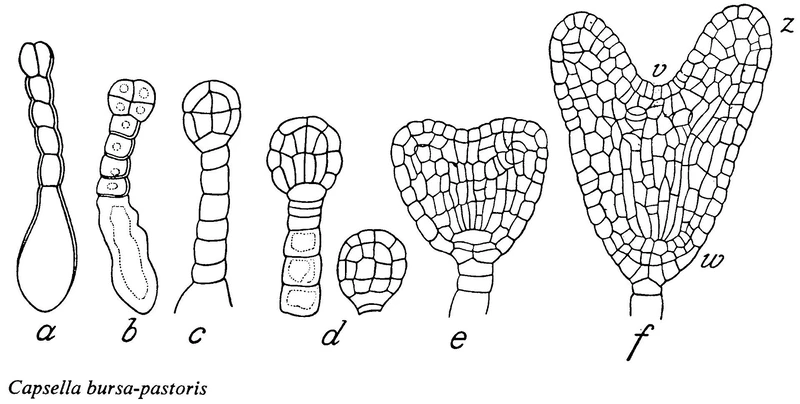

Well, only in part. The first few steps after the fertilization of a plant ovule are precisely programmed. Biologists have figured out the steps and manners in which a plant zygote (the first embryo cell) divides in two, then four, then eight, then becomes heart-shaped, and so on.

So plant growth has predefined stages that it has to go through in order to mature.

But if it was all pre-programming, some things wouldn’t add up.

The water lily seed is pushed around by random water currents, placed in random spots, at random depths, with random orientations at the bottom of the pond. No two seeds find themselves in the exact same conditions. Toss a jack-in-the-box against a wall: what are the chances that it will pop upwards and facing, say, north after landing?

Similarly, why don’t most water lilies grow in arbitrary directions, instead of always up? How do they know when it’s the right time to make leaves, or to stop making them?

The answer to such questions is feedback loops.

Without feedback (aka “self-regulation”), you get simple chains of cause and effect. To a large degree, that’s what happens with the jack-in-the-box.

There is only one way for it to act. It bursts out, facing whatever random direction it finds itself in.

Feedback is the closing of the chain onto itself.

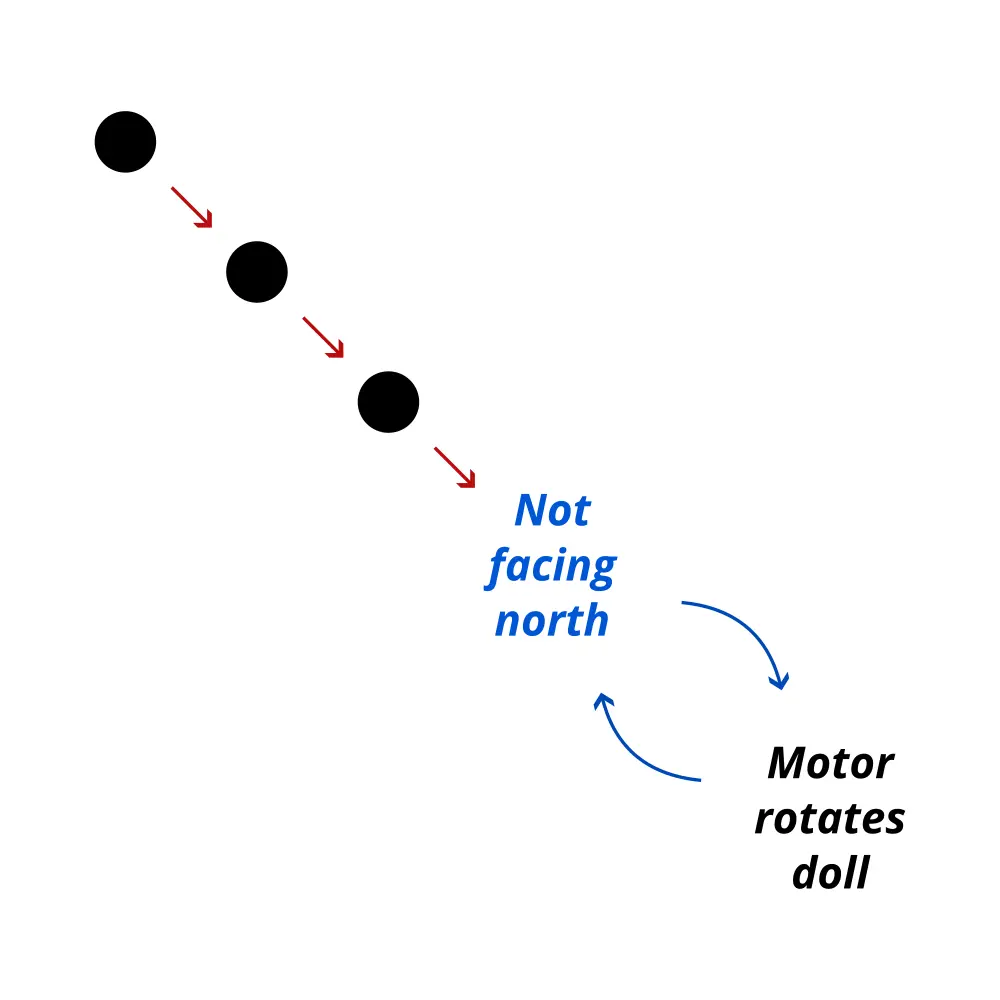

For example, if we wanted to make a “smart” jack-in-the-box toy, we could add a small compass connected to a motor to rotate the doll. If it’s not facing north at first, the motor turns it until the compass says “north”. Feedback is precisely defined only with mathematics, but a non-technical way to put it is this:

“The very fact of being X triggers chain Y leading to a change in X”

I.e. X affects X itself.

In the above example:

The very fact of being [not facing north] triggers [the motor rotating the doll] leading to [the doll facing north more].

So Jack is able to face north even though the toy maker couldn’t possibly predict its initial orientation.

A less-contrived example you might be familiar with is the wobbly doll, or roly-poly toy.

The very fact of being [not upright] triggers [a gravity pull on its bottom part] leading to [the doll being more upright].

Self-regulation is so simple—just a recursion—yet it allows for things to happen that would have been very unlikely without it. Feedback makes the Improbable much more probable. And the marvel that is a water lily pond in bloom is nothing if not improbable.

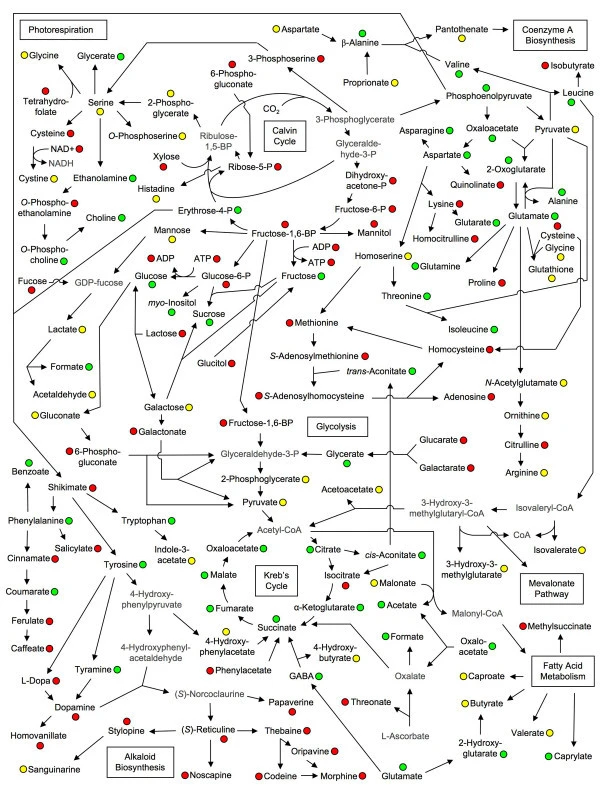

Starting small: every single cell in the water lily relies on an intricate network of feedback mechanisms simply to remain alive. You’ll find no blueprints or linear chains here. Everything affects what everything else will do next.

The right mix of chemicals, the right storage and distribution of energy, the right direction of cell division, the right flow of substances to and from neighboring cells… All these things are so improbable that there would be no hope of them happening by chance, and there are way too many factors to program their operations precisely in the DNA.

The DNA is a starting point, but the cell (and organism) has to solve its problems on its own.

When one of those myriad factors gets off the mark, chains of events kick in restoring them to their “right” levels. (Here “right” = for the current circumstances, an unpredictable state.)

So, back to the water lily seed.

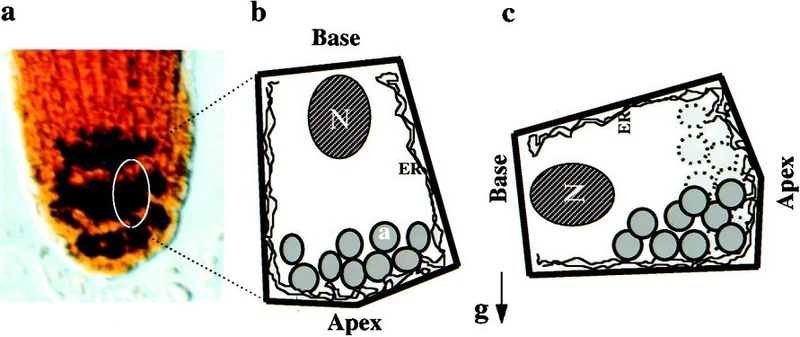

Like most plants, it has specialized cells (statocytes) containing starch packets (statoliths) that sink with gravity. In doing so they activate the release and redistribution of “auxins”, hormones that facilitate growth.

Root cells are built to grow in the direction of the statoliths (down), while the cells in the plant’s stem grow in the opposite direction (up).

In other words, the very fact of being randomly oriented triggers a tumbling of statoliths leading to a re-orientation of the plant so that it grows vertically.

So similar to a roly poly toy!

Feedback is what allows the water lily to find its nutrients (downward) and the surface of the pond (upward), where all the sweet oxygen and sun and honeybees are. 🐝

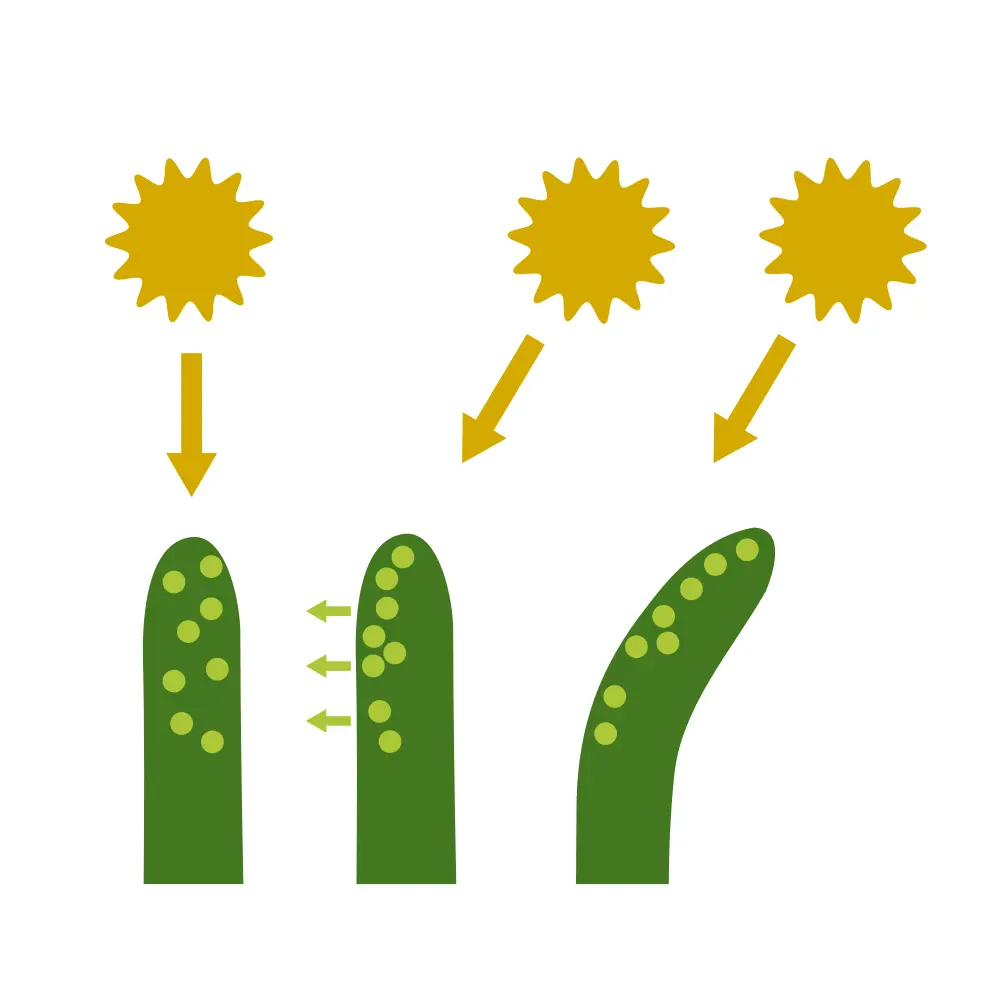

These plants (and many others) also produce special molecules that react to light. Cells at the tip of the plant’s shoot that face the sun will have a higher activation of those molecules than cells in the shade, with the effect of kicking the auxins out of the sunny side.

Richer in auxin, the shady-side cells grow longer, so that the shoot bends itself towards the light source.

Another marvelous example of feedback.

But how does the growing water lily shoot “know” when it has reached the surface, so that it can stop growing vertically and start producing its round floating leaves and flowers? Also, many water lily flowers have a daily opening and closing cycle, some preferring to open during the night and others at daytime. They’re also gender-switchers.

Do they have alarms set inside them, or pre-written calendars to pick the “right” days to do these things?

Of course, these are rhetorical questions. Most of these processes fall under the category of “photomorphogenesis”, the light-based creation of form: self-regulation. E.g. certain proteins (cryptochromes) react to blue light to regulate the plant’s circadian rhythm.

These and many other mechanisms allow the plant to infer its current circumstances and, if its state turns out to be too far from an ideal range set by the genes, chains of hormone transmission activate, eventually bringing the state of the plant back towards its ideal.

(We’ve only just scratched the surface, but it’s time to wrap up.)

Think about the sheer impact of this concept of feedback. Cut off any one of those loops, preventing a part from regulating itself, and the plant will be at the mercy of whatever random conditions it finds itself in, unlikely to survive, let alone thrive. The plant’s DNA isn’t a script to be executed, then, but a survival kit. It sets up the feedback mechanisms, and the plant uses those to improvise.

From seed to embryonic shoot and rhizome

to sinuous, vertical stem

to leaves on the tranquil surface

to a symmetry of pink-white petals

to the fruit and the birth of a new growth cycle…

…at each step, at every level of organization, in every ephemeral condition, a water lily—and all other life forms—is the transformation of extremely improbable phenomena into reality by means of feedback loops.

Feedback sharpens the possible. Beauty is self-made. 💠